ETH historic building renovated to current-day standards

An ETH Zurich architectural centrepiece – the machine laboratory– has been renovated. The historically significant machine hall has been extensively restored to its original condition. The renovation provides ETH with additional space for research and teaching.

The architects’ remit was clear: to ensure that the building complex could continue to be used for the next 20 to 30 years, remove any contamination and address structural deficiencies – while meeting the latest fire protection and earthquake safety standards. The entire building complex consists of the machine laboratory, machine hall and district heating power plant. “The renovation was extremely challenging for various reasons. I am really pleased to see the finished result ten years later and finally see the premises put to full use by ETH again,” says Ulrich Weidmann, Vice President for Infrastructure at ETH Zurich.

The renovation of the district heating power plant was already completed in 2021 and coincided with the opening of the Student Project House. Students have since been able to use the more than 1,200 square metres of space provided by the building in Clausiusstrasse to develop their own innovative ideas and projects, and in its workshop build prototypes using 3D printers.

Machine hall shines in new splendour

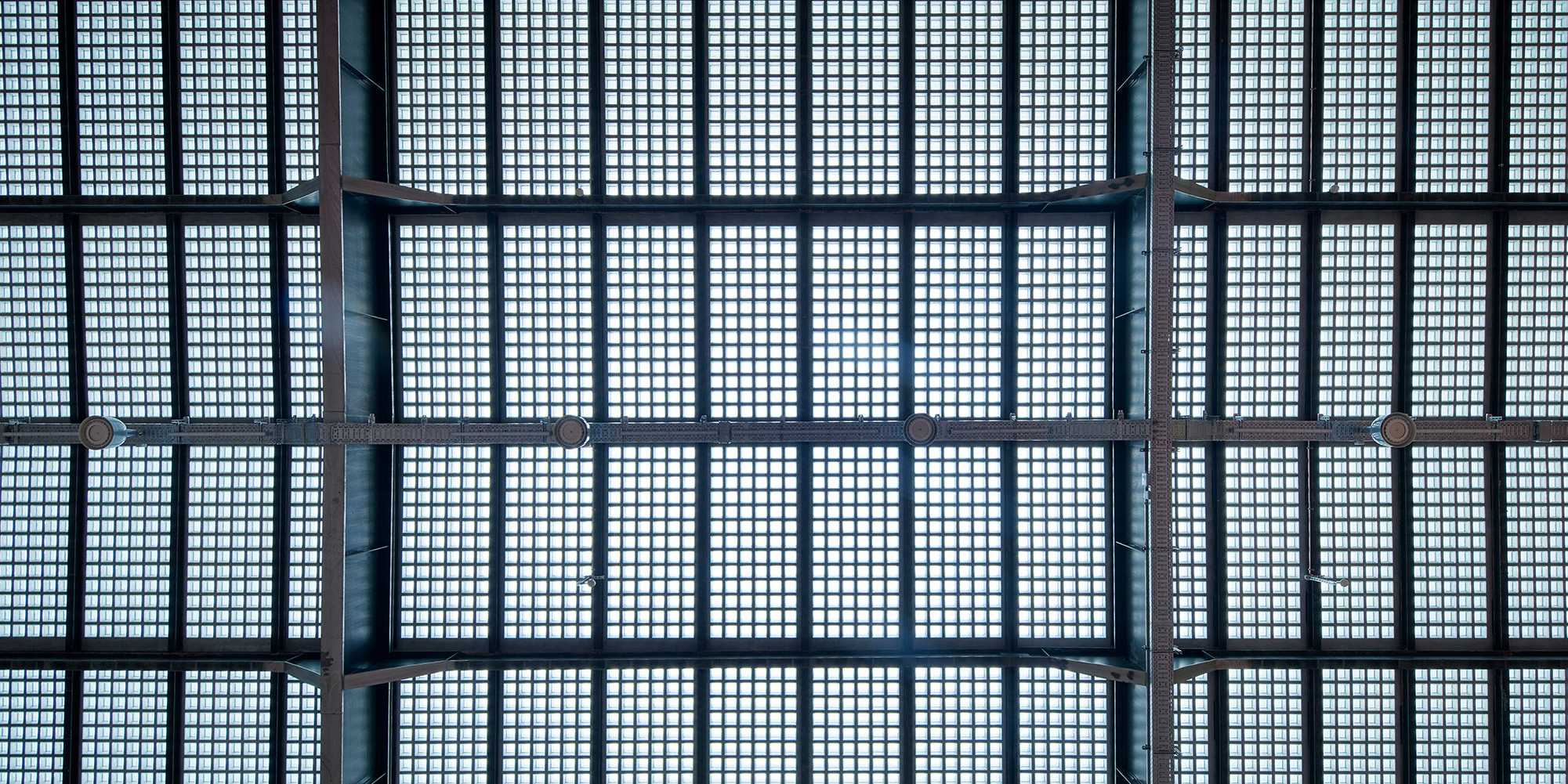

The glass prism roof is a special feature of the machine hall. It had been covered over the years due to leakage. When the architects uncovered it, they were astonished to find about ten different glass block elements. These glass prisms were barely a third of the thickness of those in use today. The renovation complies with current-day standards while restoring the influx of natural light and encouraging its flow throughout the building again. What’s more, large windows on the lower floors of the teaching building provide a direct view into the machine hall, making teaching and research visible to passers-by.

Robots instead of heavy machinery

One other remarkable feature of the newly renovated building is the former technical bridge between the teaching building and district heating power plant that appears to float in space. The architects increased the capacity of the now empty machine hall from 50 to around 300 people by replacing the former boiler in the district heating plant with a new interior structure in the form of a four-storey gallery system that complements the emptied hall. “This structure offers more open space and encourages interaction – precisely the kind of infrastructure we want to see more of at ETH,” says Ueli Weidmann.

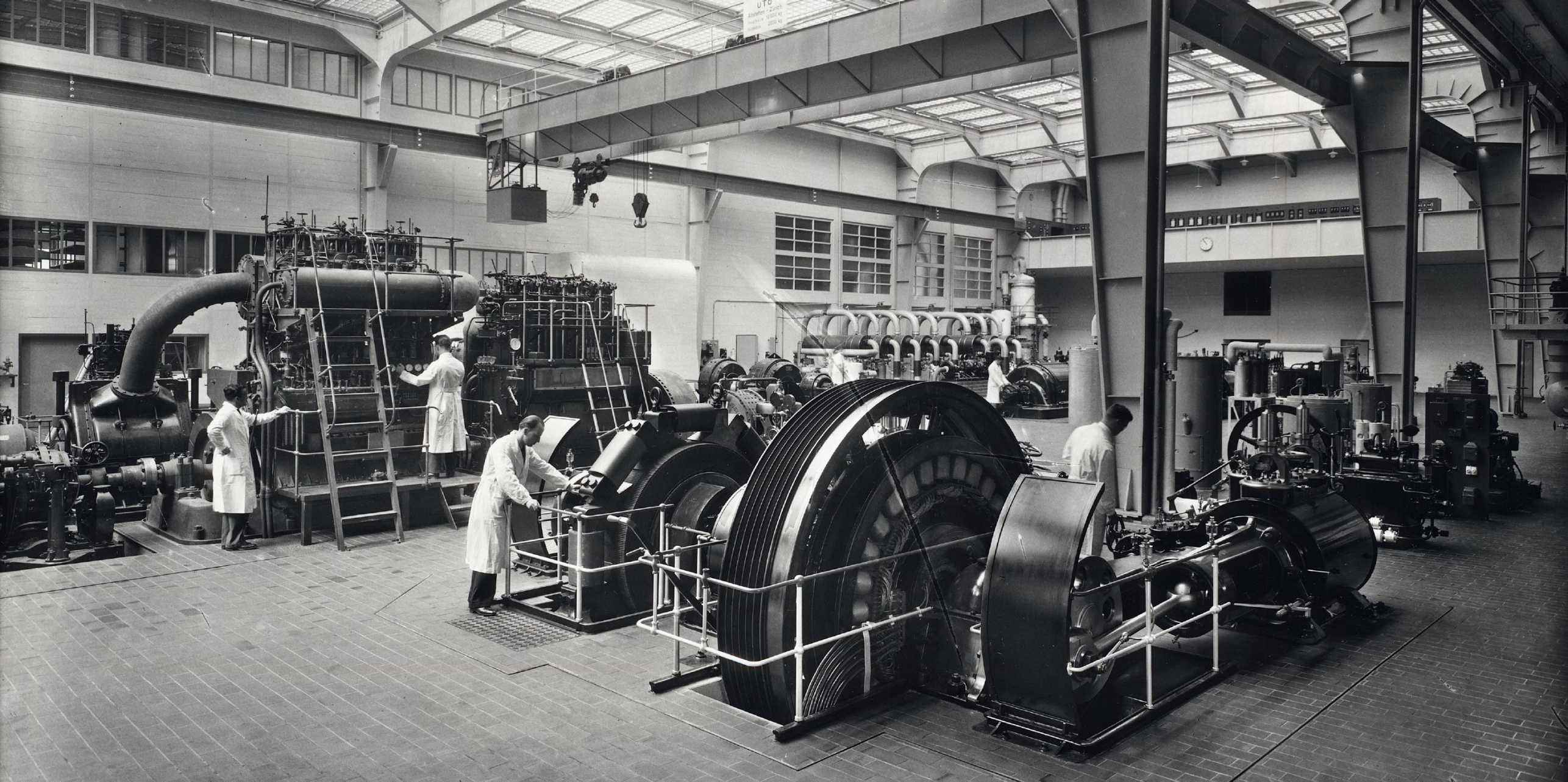

In contrast to the heavy machinery and steam turbines previously used in the listed machine laboratory, researchers will in future use the large and centrally located hall to work on the development of robotics. ETH Zurich’s RobotX initiative aims to bundle its expertise in the field of robotics and make it visible to the outside world. Drones, walking robots, autonomous vehicles and smart robots are consequently expected to populate the machine hall as early as 2024.

Restoring the historic building

The original building dating back to 1900 was designed by architect and Semper student Benjamin Recordon. It went on to be expanded in the 1930s by Otto Rudolf Salvisberg. As an ETH professor, Salvisberg trained the next generation of architects, thereby leaving his mark on Swiss modernism. The extension of the building complex was Salvisberg’s first public commission after his appointment. He had all building elements reminiscent of historicism removed and gave the machine hall and district heating power plant a functional, purposeful and clear design. Over the decades, however, this clarity and spatial generosity was compromised by crowded rooms, laboratories and offices, temporary facilities and pragmatic room extensions. These superfluous building elements have now been removed during the renovation, restoring the building’s original simplicity.

The Zeitgeist of modernity is also expressed in the building’s exterior appearance – especially the district heating power plant’s high chimney and cooling tower. These two building elements appear as one and are in stark contrast to the university’s tower and ETH Zurich’s dome. “Salvisberg placed an emphasis on the building’s technical aspects, which suits ETH very well. Since the 1930s, the high chimney and cooling tower have been an integral part of Zurich’s ‘city crown’," explains Ueli Weidmann. “Itten+Brechbühl AG did an excellent job of the renovation, capturing the spirit of the historic buildings and transforming them into a modern complex.” This success is unsurprising given that the company was founded in Bern in 1922 by external pageOtto Rudolf Salvisberg and Otto Brechbühl.