Wanted: names for exoplanets

They are called CoRoT-4 b or OGLE-2005-BLG-390L b – exoplanets often have scientific designations that are impossible to pronounce. Now the International Astronomical Union (IAU), working in collaboration with the citizen science project Zooniverse, has announced a public competition in which the 30 most popular exoplanets from a list of 305 will be given new names.

ETH News asked Kevin Schawinski, professor of astrophysics and co-founder of the citizen science platform, and Sascha Patrick Quanz, who as a senior scientist conducts research into exoplanets, what they think of the idea.

Which is your favourite exoplanet and what makes it so special?

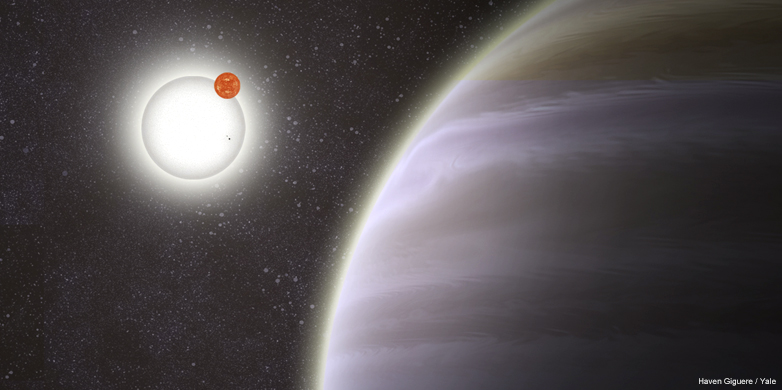

Schawinski: My favourite exoplanet is PH1b, which was discovered by citizen scientists on the Planet Hunters platform. PH1b is a true enigma, especially if we hope to understand how such a planet is formed. PH1b orbits around a binary star, which in turn orbits around a second binary star. Thus, when you look at PH1b in the sky, you don’t see just one sun or even two suns, but four!

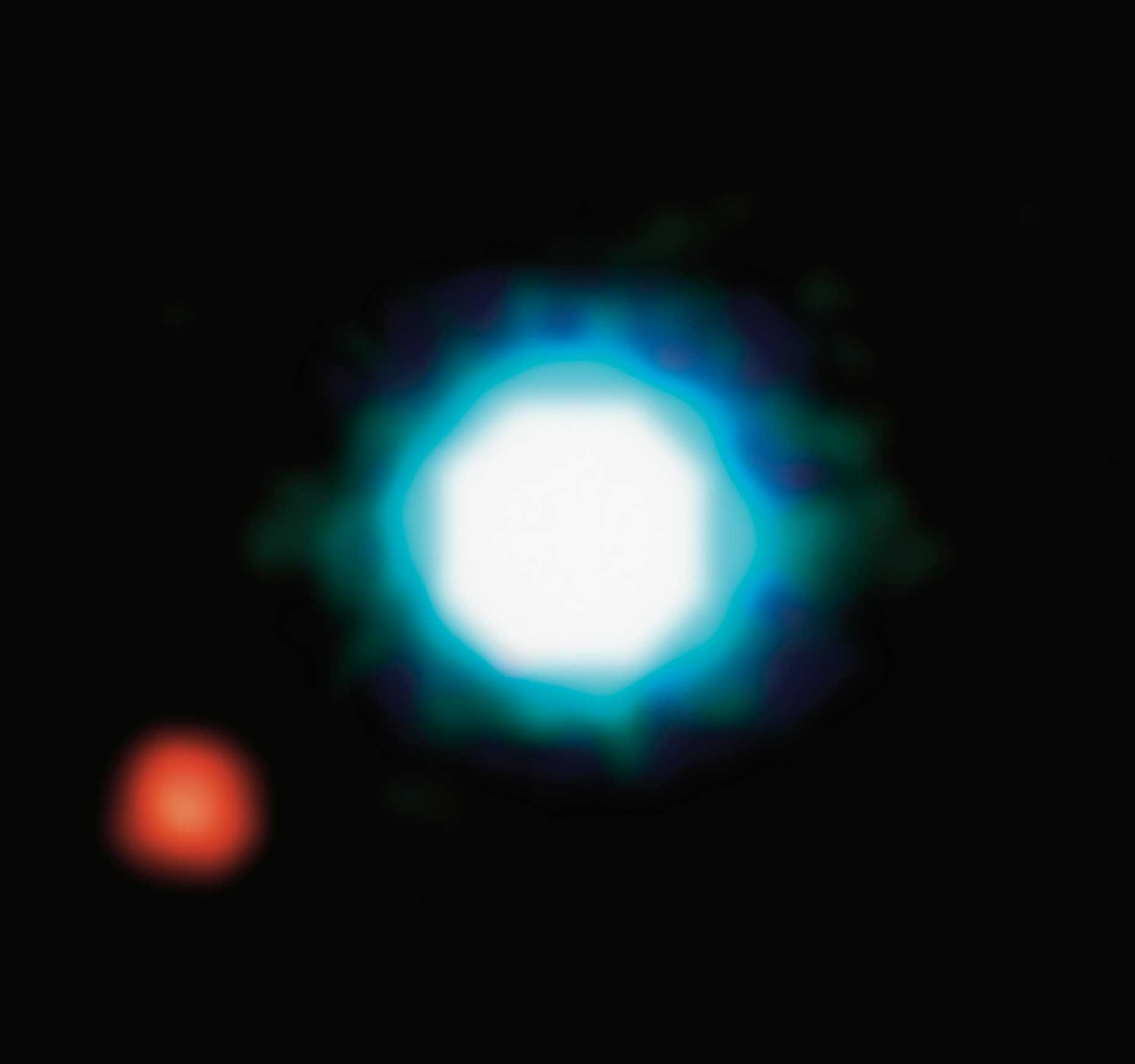

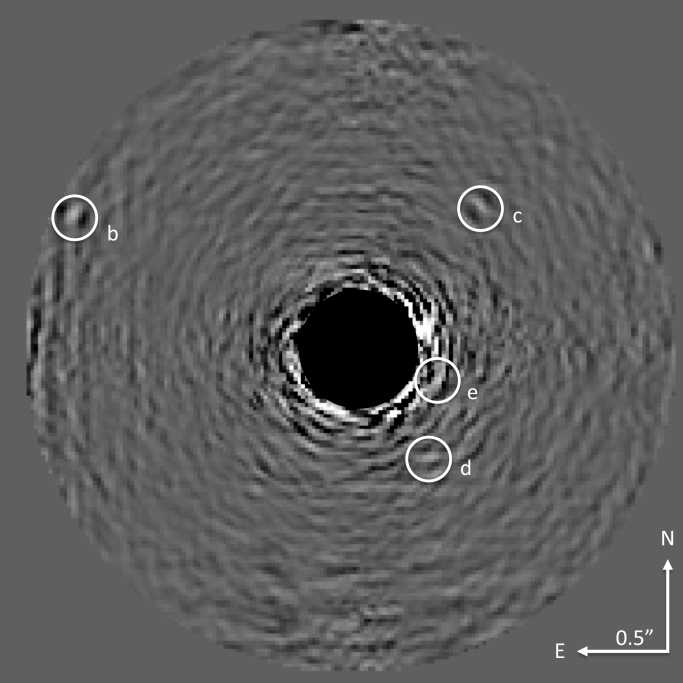

Quanz: My favourite planetary system consists of the four gas giants that orbit around the star HR8799. Each of these four exoplanets is much heavier than Jupiter in our solar system and needs between 50 and 500 earth years to orbit around the star. The special thing about them is that today we are able to capture images of them using the most powerful telescopes we have. These photos help us analyse the composition of the atmosphere on these exoplanets.

Have you thought about a new name? What would you suggest?

Schawinski: I have always expected the general public, using the internet, would come up with some names for the exoplanets. The ‘wisdom of the crowd’ effect brings unbelievable advantages to many things. One of them is that lots of people working together can come up with a better name than I could do myself.

Quanz: To be honest, I haven’t spent much time thinking about it... I should probably discuss it with my children – they’re more creative than I am.

What is your opinion of the IAU initiative?

Quanz: I like the initiative. It's important that the general public has access to our research and is able to see what we do. With this naming scheme, many people have the opportunity to start thinking about what exoplanets are. In doing so, they discover just how many planets have been found in our cosmic neighbourhood and the properties they possess.

Schawinski: I agree with that. A stronger integration of the public into the scientific community is a positive thing. When they are given understandable names, these far-off worlds – not only the exoplanets but also science itself – become much more real and tangible.

The general public seems to show great interest in reports about exoplanets. Why do you think this is the case?

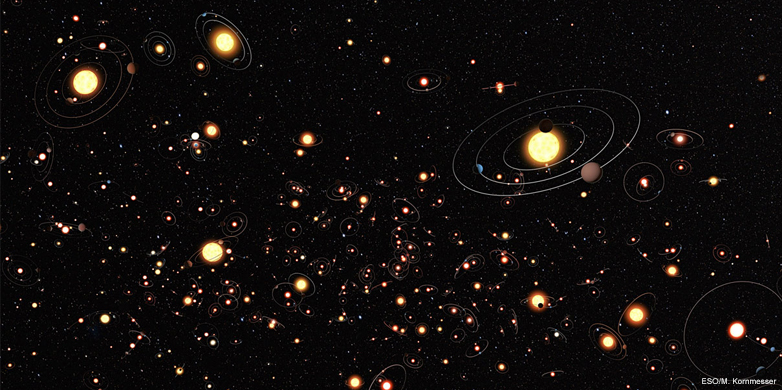

Quanz: It’s partially due to the question of extra-terrestrial life and our place in the universe. Ever since we have been able to prove scientifically that there are countless planets out there, the question arises as to whether some of them have conditions that could support life. This question arises because most of these planets are very similar to our Earth, at least in size and mass. Looking into the night skies and knowing that virtually every star has planets orbiting around it is a fascinating thought.

Schawinski: For me, it's clear. Every newly discovered exoplanet brings us closer to a planet similar to our Earth – and on which there may also be life. If somewhere out there, a form of life exists that is not associated with Earth, that would be the biggest discovery of all time.

What are the next big steps in the study of exoplanets? Which questions are still unresolved?

Schawinski: The next step is to find Earth-like planets in our environment. But with the – justified – hype about exoplanets, we should also not forget about our own solar system. A mission to the moons of Jupiter or Saturn, on which there may also be life, would be fascinating.

Quanz: The more planets we find, the more questions arise, which in turn means we have an extremely large number of questions to answer! We should clarify how many planets orbit around their stars at a distance that would allow them to have liquid water. Liquid water is often referred to as a condition for life as we know it on Earth and may make it possible on other planets.

About the people

Kevin Schawinski was born in 1981 in Zurich; since 2012 he has been an Assistant Professor of the astrophysics of galaxies and black holes at the Department of Physics. His primary focus of research is the co-evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes. He is also very active in citizen science and the direct involvement of the general public in scientific research. (ETH Life, 21 January 2013)

Sascha Patrick Quanz is a Senior Scientist at the Star and Planet Formation Research Group within the Department of Physics and has been at ETH Zurich since 2009. He researches the physical and chemical properties of extrasolar planets and their formation. (ETH Life, 28 February 2013)