Citius bob on the starting block at Sochi

The Citius bob was co-developed between 2007 and 2012 at ETH Zurich, now it is starting again at the Olympics on Sunday. The bob experts at ETH think with significantly better odds than in Vancouver.

When the Swiss two-man bob men’s teams begin racing on Sunday, ETH Zurich will be joining them on the starting block. This is because the Citius bob used by the Swiss team in Russia for all six race sleds was co-developed at ETH Zurich between 2007 and 2012. Martin Elsener from the Department of Material Science’s workshop has been involved from the very start and is following with excitement: “The chances of a medal – particularly in the men’s two-man bob – are very good at these games.” And Elsener knows what he is talking about: during the development of Citius, he not only co-built the new bob, but has also ridden it countless times. “I was the bobber in the ETH team, so it made sense to put me in the Citius,” he says, laughing.

Unlucky in Vancouver

The Citius bob was built for the Vancouver Olympics in 2010, where the Swiss bobbers, however, were not successful. Whistler’s track was also so dangerous that some pilots refused to take part and the Citius bob was hardly used. So what has changed since then? Some changes have been made following Vancouver; for example, the four-man bob’s rear push bar has been optimised with a slight bend. The leaf springs that influence the pivot of the bob’s front parts were overhauled and the rear damping had to be removed. The damping was a speciality of the Citius bob, but the new regulations no longer allow it. Elsener is convinced that this modification should ensure that the costs for an already expensive sport do not explode: “The damping, although only a small detail, is very expensive. We want to prevent the possibility of some countries no longer being able to participate in competitions due to the cost.”

Practice makes perfect

When Elsener is asked about the reasons behind the failure in Vancouver, he believes that it was due to the fact that the test phase of the new bob before the Olympics was too short rather than a fault with the material. Bobsled pilots need to get used to a new bob. “The pilot must make three different steering movements in 1.5 seconds, depending on the bend. A good pilot can do this automatically and intuitively. In the case of a new bob, they need to adapt their driving behaviour,” explains Elsener.

The number of trial runs also has an impact on the material: “The runners on the Citius bob are optimised so that they have particularly low friction on ice; every runner gets better the more frequently it is driven.” The material becomes harder and therefore faster through impact with the ice. The runners for any bob are a science in their own right; for example, the cross-radius of the runner depends on the constitution and temperature of the ice, and the tightness of a track’s bends also plays a role in selection of the right runner. It is hardly surprising then that the Swiss athletes packed several purpose-made runners for the difficult track and demanding climatic conditions in Sochi.

Fewer driver errors thanks to the simulator

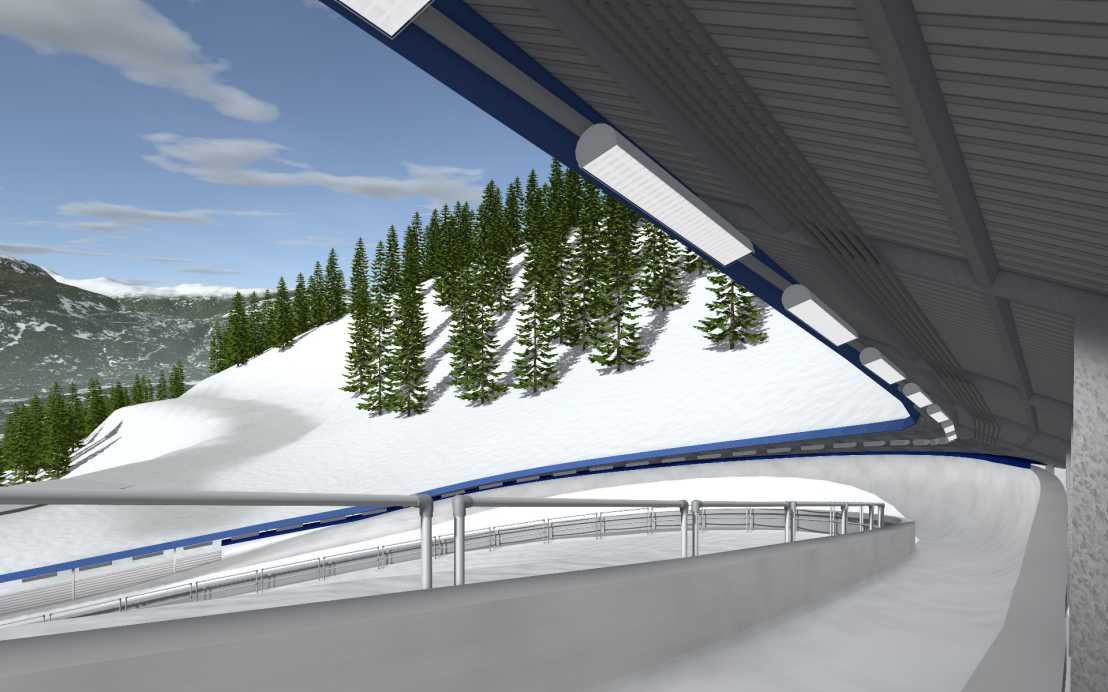

In addition to the Citius bob, the Swiss bobbers also have another advantage: they are more familiar with Sochi’s track than many other athletes. Professor Christoph Glocker from the Institute for Mechanical Systems and his doctoral student Georg Rempfler constructed a track simulator using complex calculations. This meant that Beat Hefti, for instance, was able to train in the summer on dry land. “I was impressed by how cleanly Hefti drove in the simulator right from the first run. He was very well able to implement visual impressions directly to steering movements,” says Glocker. Of course, the simulation cannot replace training on ice, but as it is based on data from the Citius two-man bob, pilots can develop a feel for how the bob will behave on Sochi’s track. “An analysis of driving errors is certainly possible by simulation,” explains Glocker. But he also points to another advantage of the simulation: with its help, tracks can be tested very realistically. “We can prove, for example, that the Whistler track in Vancouver had very dangerous passages where there was the risk of a bob overturning,” explains Glocker, not without pride.

Glocker became interested in the Citius project through his admitted long-standing enthusiasm for rollercoasters. Today, he knows more about bob runs than many others and as a result is on the track committee of the international bobsleigh federation (FIBT), which monitors the various aspects of track safety. It also seems as if the scientists are not able to escape a passion for bobsledding once it has taken hold. Even though the Citius project is now finished, ETH retains a link to the sport: Rempfler is doing his bob pilot licence to find out what bobsledding actually feels like, and Elsener carries out race material inspections on behalf of FIBT.

For more information on the Citius bob