Adding values through digitisation

Concern over the influence of machine learning in architecture is exaggerated, argues Adam Jasper. The challenge is not to oppose quantification, but to take charge of what is quantified.

I recently accompanied a group of architecture students for a few days of a seminar week. We visited people in many different professions in order to understand how machine learning and artificial intelligence affect their working lives. Do the students have cause for concern?

If one thinks of a profession in terms of a set of skills honed for performing specialised tasks, then the threat posed by technology is real. It is difficult, even with constant retraining, to outpace the speed with which new platforms and new techniques render such skills redundant. But there are alternatives. One possibility for architecture is to broaden the definition of the architect’s role, rather than limit it through technology.

Architect of the money bag

In John Evelyn’s 17th century account of architects and architecture, the title of “architect” is given to multiple roles in the building industry. There’s the architectus ingenio, who has mastered all the arts, from geometry to hygiene, from history to optics. There’s the architectus manuarius, who does a lot of the actual building. And then there’s the architectus sumptuarius. This is the architect of the money bag – that much vilified figure of architectural history, who we today recognize as the property developer.

Property developers are not greatly celebrated in architecture discourse, because a developer is motivated above all by the predicted return, and is notoriously prepared to erase all the creativity and spatial intelligence in an architectural project in order to maximise it. But up until now, developers have had only a very crude and unreliable set of tools for measuring the architectural quality of spaces.

Blind algorithms

Zillow, one of the largest real estate portals in the United States, with millions of transactions on its books, proudly noted in a press release in 2016 that it was capable of predicting prices within 6% accuracy, roughly half of the time. Hardly impressive considering the gigantic amount of data involved! A cursory look at the algorithm makes clear how blind the process is. Certain kinds of data are easy enough to gather: the number of square metres of interior space, the number of bedrooms, the year in which the house was built, the average price in the neighbourhood. None of this information says much about the house itself. Such predictive systems have no capacity to recognise the qualitative differences that are so influential in human decision making. Factors such as the proportions of rooms, ceiling height, the nature of the materials, ambient noise, or even such obvious facts as aspect and natural light – precisely those things a human would care about – are not included in calculations.

Making smart use of data

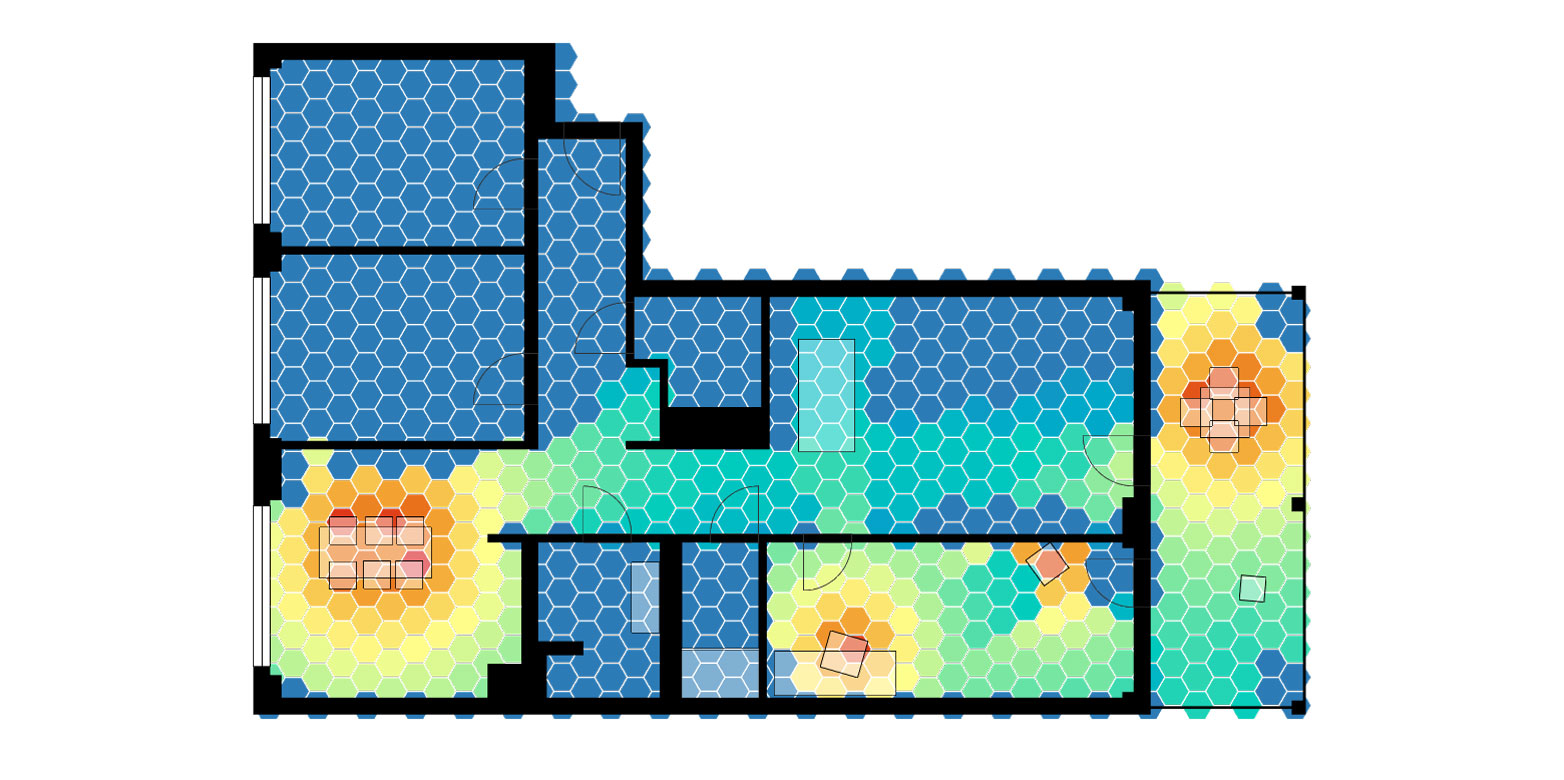

Imagine, however, if one could use the available data to infer whether an apartment would feel cosy or cramped, if rooms would seem spacious or cold. It is precisely this task that is at the centre of the work of an ETH startup called Archilyse. Archilyse does not gather more data than its competitors, but attempts to do so more intelligently, to provide developers and architects with better tools for predicting the final value of a property. Using floor plans and urban contextual data, the company attempts to infer the subjective qualities of a space. Archilyse can, for example, make visible where and how much noise to expect in an apartment.

“In spite of the hype, machine learning will not perform the task of good design.”Adam Jasper

If maximising profit could suddenly be understood not as maximising space, but as maximising the quality of space, development might suddenly take on a rather different aspect. It is here that machine learning comes in, for it can help develop tools with which predictions regarding the quality of space might be made. If ceiling heights can be proven to matter, if careful modulation of space can be shown to work, if natural light makes money, developers will pay attention to them. Such tools would change the metrics that constrain architecture, they would equip talented architects to make a case for intelligent designs. But it is up to the experts themselves to use these tools.

Professional fine-tuning

Of all the professions that the students visited in the seminar week, it was a violin maker who was most optimistic about the future. Surrounded by violins, some of them made at the same time as John Evelyn’s account of architecture was first published, he also had a computer on his desk that he used as a matter of course for sensitive calibrations for the instruments. He wasn’t threatened by computation, because the ends that it served were always his own – to better make violins.

Passivity is an attitude that even architects cannot afford. In spite of the hype, machine learning will not perform the task of good design. Artificial intelligence will not do the work of an architect, rather, it will enlarge it.