Russia as a Challenger of the West

1 Apr 2014

By Jonas Grätz for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This chapter of Strategic Trends 2014 can also be accessed here.

Recent years have seen the rise of an uncompromising, confrontational Russia. Anti-Western and imperialist tenets have been strengthened. This development is driven by the regime’s weakness, isolation, and insecurity. From Syria to Ukraine, Russia mostly acts as a spoiler, exploiting the West’s divisions, while offering few solutions of its own. Despite its fragile power base, Russia’s regime is here to stay for the foreseeable future. Western leaders will thus have to learn to cope with this new reality.

2013 was a very successful year for Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin. Despite Russia’s support for Syria’s regime, Russia emerged as the white knight with its proposal to scrap Syria’s chemical weapons. In Europe, Putin played hardball with the EU over Armenia and Ukraine. Hosting former US intelligence contractor Edward Snowden has won Putin sympathies with many in the West, while Snowden’s revelations are eating away at transatlantic trust. Thus, while the Western world attempted to turn away from Russia and towards seemingly more pressing problems, Russia gave it a reminding pat.

Russia is thus back, though not necessarily as a responsible actor. It vows to build a ‘multipolar world order’. Yet it is interested in multipolarity only insofar as it strengthens its own power. Moscow’s designs of such an order do not go beyond corroding the power of the West and renewed imperial ambitions in its own region. The Kremlin makes its voice heard, yet it can offer few solutions for global or even regional problems. In advancing his goals, Putin is playing hard-nosed power politics, yet he has also sharpened Russia’s subtler tools of influence and propaganda.

This chapter’s argument is twofold. First, with the intention being to weaken the West, Russia plays power politics mostly well-tailored to its capabilities. Second, these ambitions are driven by domestic politics – the survival of the personalized regime that is ‘Putinism’. While Putin does not face a credible domestic challenger, the advancement of democratic standards of governance in neighbouring states presents a threat to Putinism. To prolong and solidify his rule, he thus has to keep Western influence at bay. Foreign policy has become an even more important way of distracting attention from domestic problems in times of declining economic glory.

To analyse the tools, conduct, and limits of Russia’s foreign policy towards the West, this chapter will first examine the domestic drivers of Russia’s foreign policy. It goes on to look at the tools that Russia has at hand. Against this background, the chapter will look at how Russia conducts its foreign policy towards and against the West.

Understanding Putinism

Perhaps more than in other countries, Russia’s foreign policy is a reflection of domestic forces. Society’s atomization and corresponding lack of selforganization is the most important constant, giving extraordinary power to elites. In the 1990s, Russia under President Boris Yeltsin seemingly embraced capitalism and democracy, yet the power rested with elites and not with the people. Privatization improved performance, but resulted in the creation of oligarchs, a new class of wealthy and powerful businessmen that had great influence on politics. Foreign policy was almost as discordant as domestic policy, since there were many power centres.

After taking power in 2000, Vladimir Putin undertook decisive steps to establish the regime of Putinism. In its core, it is a dense, relatively stable network of elites that holds centralized political and economic power and is represented by Putin as the ultimate arbiter.

Putin’s power vertical

Putin swiftly moved to position himself at the apex of the political and economic system. Lifting his acquaintances from the former KGB and from Saint Petersburg into key political and economic positions, he could eliminate political and economic competition and established control over the media. He thereby reformulated the relationship between state and society and consequently between Russia and the world. In moving swiftly to neutralise Russia’s multiple and discordant social forces of the Yeltsin era, Putin aimed to improve stability.

Putin put his paradigm down in a newspaper article published on New Year’s Eve of 1999. The Russian idea should be some combination of patriotism, “great power-ness” (derzhavnost), statism, and solidarity rather than individualism. But his key proposition was that no political campaigns should be allowed to destroy this “nascent consensus”. Thus he had to rein in rival power centres at any cost in order to turn Russia into a strategic actor again.

To solve problems, Putin relied on personalized power and on command-and-control rather than on institution-building and markets. This corresponds with much of Russia’s economic reality. Reliance on point-specific natural resources favours economic centralization, as do the remnants of Soviet industry. With Russia’s relatively primitive economy, disciplining the oligarchs had little short-term cost, while bringing immediate dividends in terms of political power, higher tax revenue, personal wealth, and public support.

Putinism worked reasonably well during the 2000s, owing to Putin’s strong tactical skills and benevolent external conditions. It was able to stabilize Russia and to ensure rapid growth. Sharply rising oil prices were the key in this respect. Fixed investment kept rising, as did pensions and wages. In large cities, a wealthy class emerged. Macroeconomic management was carried out in a very professional way. When the 2008 economic crisis hit Russia, the impact was worse than in other emerging economies, but it did not plunge Russia into a crisis.

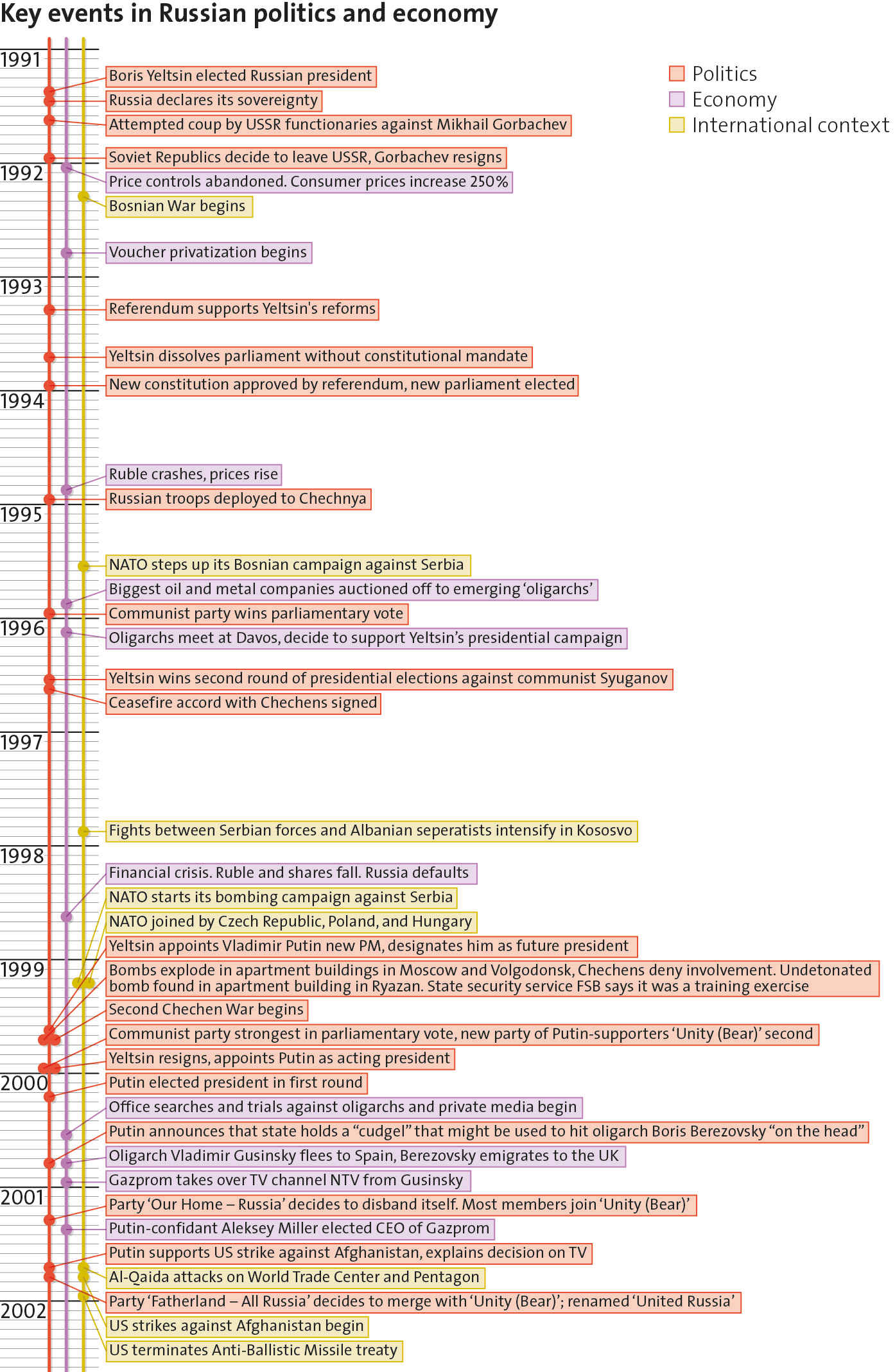

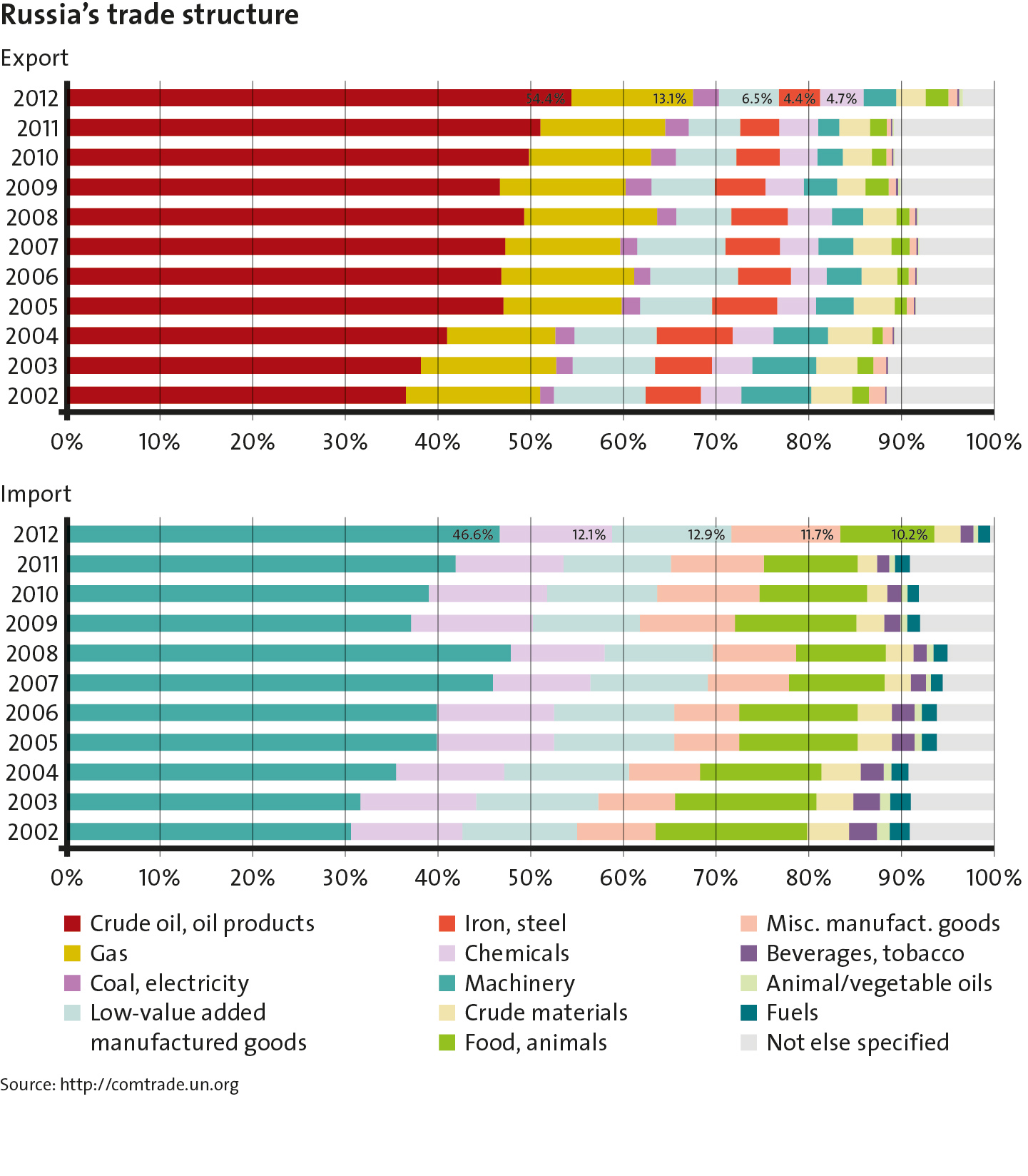

Timeline of key events in Russian politics and economy

However, investments in the future fell short. Putinism runs counter to the creation of an effective state, hollowing out formal state institutions and keeping economic forces under political control. Putin could not provide effective healthcare, modernize the economy, or invest in much-needed infrastructure. The share of oil and gas in exports only kept growing. Capital flight remains high, and the same is true of the notorious ‘brain drain’. By the end of the 2000s, Putin was keeping power at the expense of domestic development, forcing him to change his strategy for legitimation.

Legitimation: anxiety and conservatism

All in all, Putin does not need to resort to high levels of coercion to stay in power. As long as the economy grew rapidly, economic success supported Putin’s regime. However, as Putinism brought decreasing returns towards the end of the 2000s, the strategy for gaining support was increasingly built on anxiety. Whereas in 2007 “Putin’s plan” was still deemed sufficient to inspire hope in the country’s future, “we have something to lose” would become the defensive rallying slogan of Putin’s supporters by 2012. And it worked. “Stability” and the corresponding fear of economic downturn and political chaos is still Putin’s most important currency of specific support, while the opposition faltered.

In Russia’s collective memory the 1990s became synonymous with this instability. Not least because of Putinism’s control over TV, this period is now being remembered solely as a period of chaos and the “deepest downfall” of the country. Analysis of the ills of Soviet power has taken a back seat. To foster the idea that Russia is on the right track, Putin succeeded in discrediting the West as a potential development model as well.

Correspondingly, in his third term Putin began to formulate a more coherent ‘conservative’ ideology to win support among the poorer, traditionally-minded electorate. In Putin’s view, as the West shuns its Christian values, Russia will emerge as their new home. The idea is mainly backward-oriented and hence has no devices to cope with the reality of the world’s current interconnectedness and its problems. Yet it connects with the longing of society for reduced complexity in times of rapid global change.

To deflect attention from domestic issues, the US was resurrected as Russia’s main enemy in the public perception. Anti-Americanism is cheap to craft, as it connects easily with the prevalent categories and perceptions of the Russian population and since the US’s global presence provides an ideal target. Words had to be connected with deeds where power resources allowed. Russian foreign policy became increasingly anti-Western and imperialist in its neighbourhood.

The foreign policy toolbox

Vladimir Putin’s Russia has only few foreign policy tools at hand, yet it uses them exceptionally well. These tools include the opportunity to shape global political developments via nuclear and conventional military power, energy and economic attraction, propaganda, and covert action. Each of these factors will be examined in turn.

The UN Security Council is still commonly regarded as the main arbiter deciding on the legitimacy of coercive measures in the international system. This reality is elevating Russia to the status of a global power. Alongside the US, Russia has clearly emerged as the most important actor in the Security Council. The other permanent members are either allies of the US or chose to take a low profile, such as China. Since it puts Russia on an equal footing with economically and militarily stronger states, or even above them, Moscow has a keen interest in preserving its status in the Security Council. This also exposes the Kremlin’s calls for a “multipolar world order” as selfserving, since Russia fiercely opposes reform of the Security Council.

Military power

Russia is the only state in the world that possesses a credible nuclear second-strike capability against the US. It spends an estimated 40 % of its defence budget on its about 1800 strategic nuclear weapons, which are being constantly modernized. Most important, nuclear weapons convey status. They allow Russia to speak to the US in the language of “strategic stability”. Furthermore, the deterrence potential is considerable, as Russia reserves the right to use its nuclear weapons also against a conventional attack. Yet as long as the US keeps its nuclear arsenal at par with Russia and does not revert to isolationism, Russia’s nukes will stay a blunt tool.

The Kremlin has thus increasingly focused on its conventional forces, especially after the war against Georgia. Whereas the armed forces were not a priority during the 2000s, Putin significantly increased funding in his third term. He embarked on a military reform that is intended to put an end to the Soviet model of a standing army and instead provide for flexible and integrated forces. The reform is giving first results in terms of improving flexibility and interoperability and is transforming the military into a state of permanent readiness. At a slow rate, new equipment is being introduced, especially in the navy and concerning offensive and defensive missile systems. Drills have become more frequent. This has improved the capability to fight local and regional wars. Nevertheless, demographics and education will remain a continuing challenge, as will equipment.

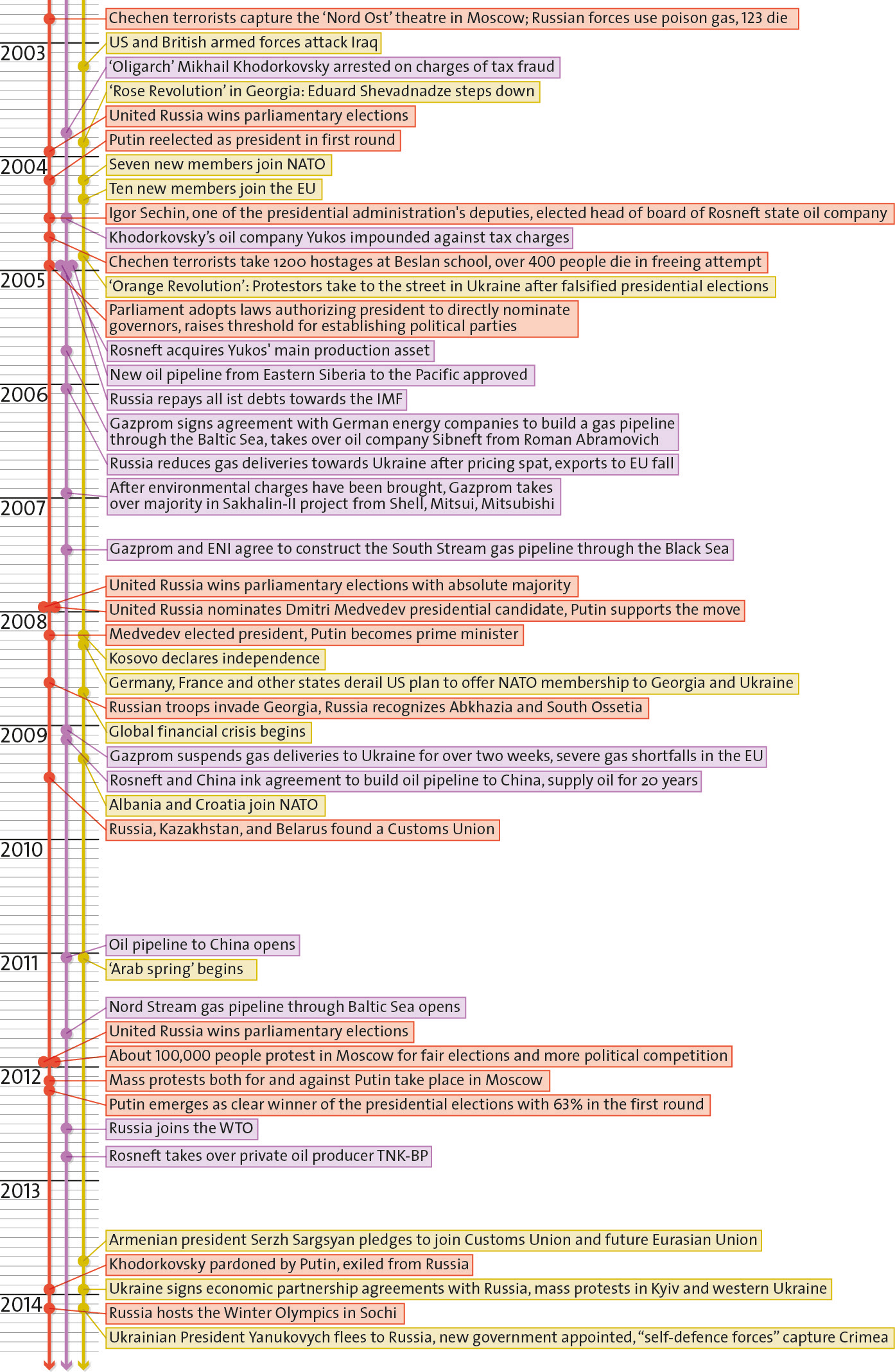

Internationally, the country’s militaryindustrial complex remains an important tool for Russian influence, as its exports contribute to technological dependence. Russia is the world’s second-largest weapons exporter, being able to provide relatively good technology at a low cost. It has also begun to sweeten arms deals with credits. Of course, countries can pick and choose on the global arms market, but investment in Soviet or Russian technology often comes with considerable path dependency, which only the largest players can break.

Energy

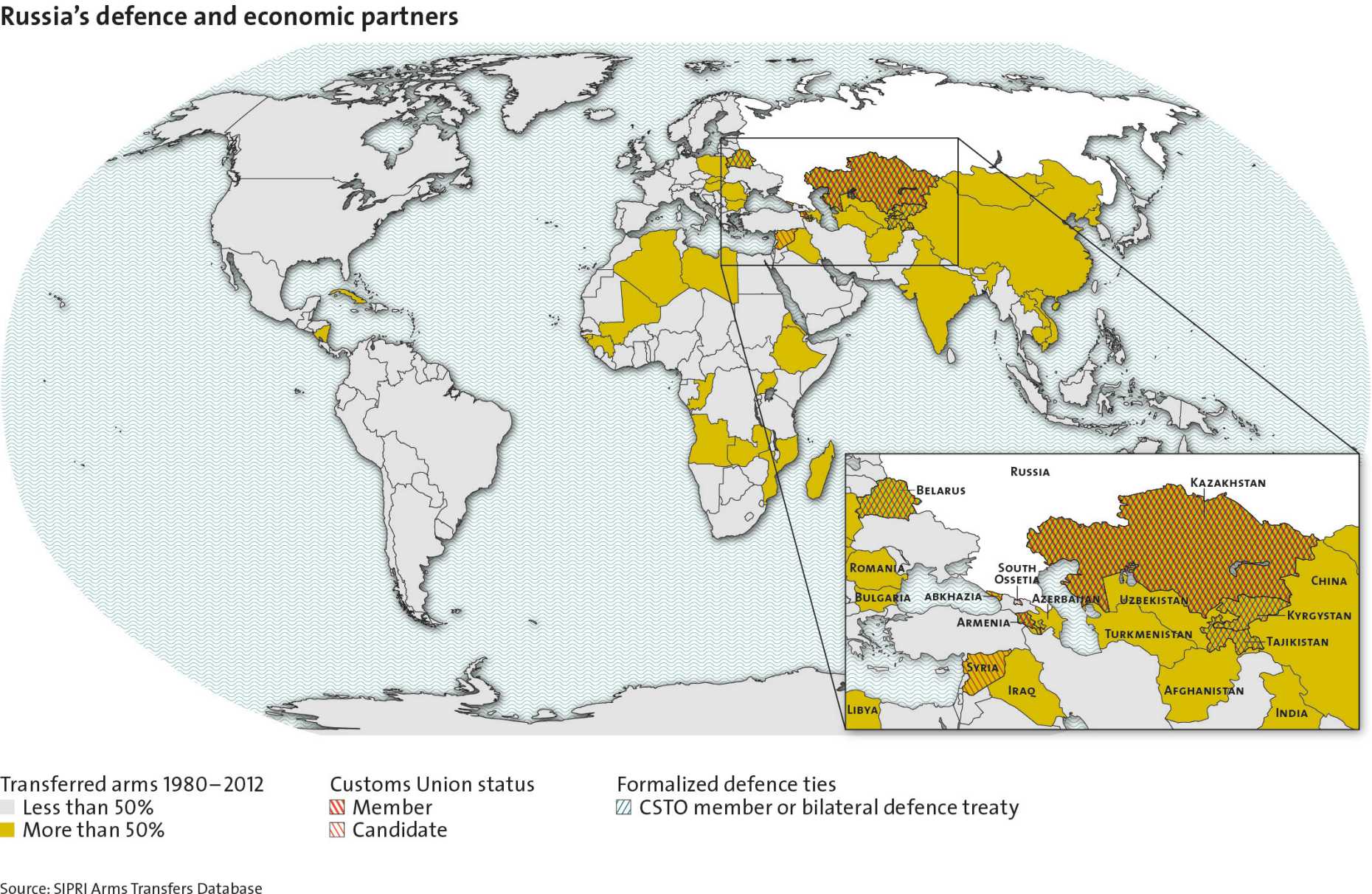

Energy is the key to Russia’s economic power. Russia hosts the world’s largest reserves of natural gas and the eighthlargest oil reserves, with much more to be discovered. Directly, energy resources provide about half of Russia’s federal budget, while contributing more than two thirds of export revenue. Between 2003 and 2008, the effects of a rising oil price contributed half of Russia’s GDP growth. Most of Russia’s exports go to the EU, which imports about one third of the gas and even more of the oil it consumes from Russia.

On top of the attraction of its energy resources, Russia’s advantage is that it can act en bloc as a strategic actor, opening the possibility for divideand-influence tactics. Putin controls both Russian energy giants and the access to hydrocarbon investment in Russia. Directing his companies to invest abroad while he controls access to supplies and investments at home allows Putin to foreclose supply alternatives and extract concessions from countries and businesses. His message has been clear: integration of the energy value chain – yes, but only on the Kremlin’s terms.

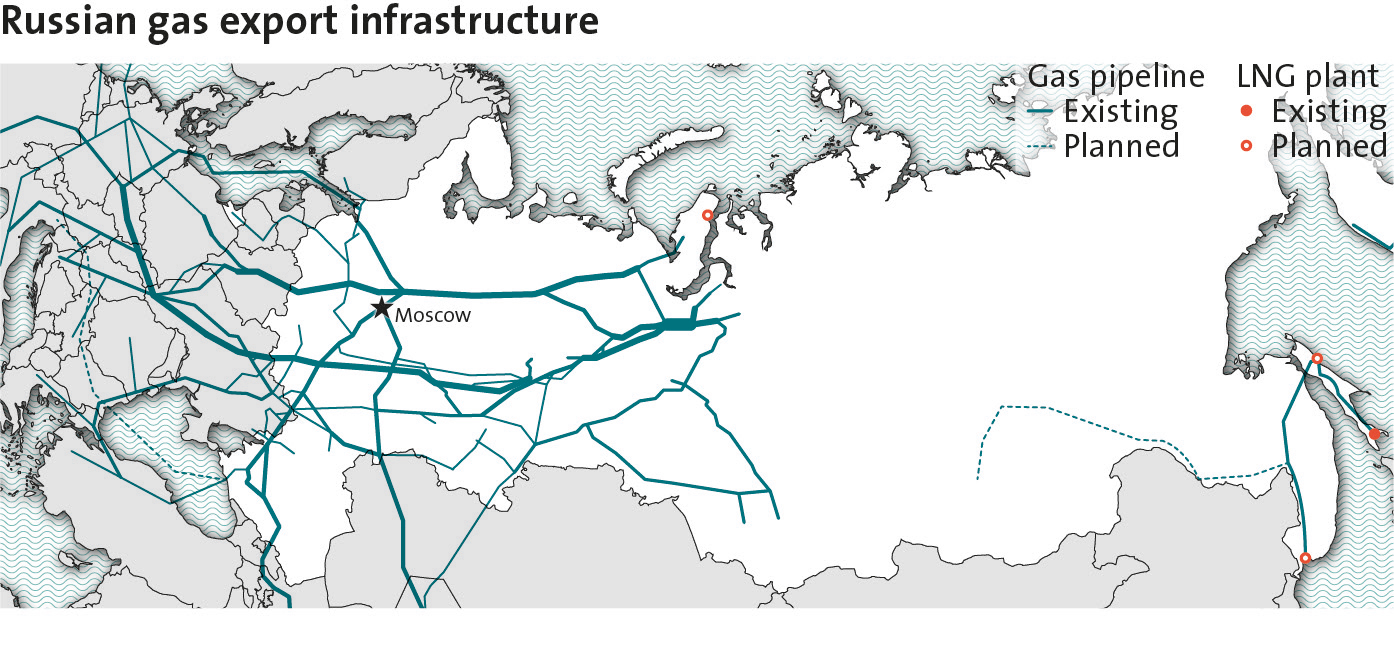

Gas supply has been more important for Putin than oil. Especially if there are no supply alternatives, profit and geopolitical influence go together smoothly. Even so, the balance has recently been tilting towards the latter. In a bid to increase Russia’s clout over Ukraine and in the Balkans, Putin not only opted for constructing costly new pipelines, but he also offered lower gas prices as a carrot.

Russia's Defense and Economic Partners

Russia's Trade Geography

The ultimate energy weapon – stopping deliveries – can be relatively costly, as the role of hydrocarbon exports in Russia’s economy and state budget is paramount. Yet this might not deter Putin from using it, which became clear in 2006 and 2009, when deliveries to Ukraine were stopped. And diversification of imports, despite all efforts, can be difficult. The knowledge that Putin is ready to use this weapon serves as a credible, disciplining threat to those dependent on Russian energy supplies.

Economic attraction and integration

Russia has gained in economic attraction, since its market for goods and cheap labour has grown rapidly during the 2000s. With over eleven million immigrants, Russia is the world’s second largest recipient of migration, mostly from poor countries in Central Asia. Economic distress in many parts of Europe and the post-Soviet space has helped to uphold the Kremlin’s clout. Opening up and shutting down market opportunities has thus developed into a potent foreign policy tool for the Kremlin. Even though Russia became a member of the WTO, the latter is too slow and clumsy to blunt this vital tool.

Taking advantage of this economic pull and its energy resources, Moscow launched the ‘Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia’ in 2010. It emerged as Russia’s main vehicle in the post-Soviet space, as it is the most ambitious integration project in this context yet. It abolished internal tariffs, implementing a common customs code and is run by a ‘supranational’ body, the Eurasian Economic Commission located in Moscow. Decisions are taken unanimously by the Commission’s council, where each state is represented by one member. By using its carrots and sticks, Moscow won Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan as new accession states, whereas Ukraine resisted. The Kremlin plans to turn the Customs Union into the Eurasian Economic Union by 2015.

It is easy to mistake the Customs Union for an organization similar to the EU, a view promoted by the Kremlin. Russia has undoubtedly found a new formula of combining economic carrots like lower energy prices with a formal integration format, enhancing its attractiveness. But its members are too dissimilar to allow for EU-style decision-making. Russia’s GDP is ten times higher than that of the next largest country in the union.

Russia has also taken the lead, drawing complaints from both Belarus and Kazakhstan. They have criticized the Commission for being too politicized and Putin for being too eager in recruiting new members with questionable economic credentials.

Diplomacy, societal ties, intelligence services, and propaganda

Russian diplomacy is based on a sound analysis of the opponent’s weaknesses and own abilities and is highly professional. But what sets the Kremlin apart is its ability to combine diplomacy with a wide range of economic, military, and social tools and its uncomplicated approach to using these.

In the post-Soviet space, the Kremlin can exploit human ties. Despite the fact that the Kremlin preaches strict adherence to state sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs, it has adopted a law and a strategy to support “compatriots” abroad – in practice everyone with past ties to Russia or the USSR. To fulfil this aim, the Kremlin sponsors various organizations aimed at promoting the common roots of a supposed “Russian world” and is fighting against “falsifications of history”.

Russia’s intelligence services continue to be an important resource for realizing foreign policy goals, even more so as they inherited close ties to sister services in the post-Soviet space. Their task is not confined to gathering information and identifying targets, but they also carry out covert operations. With a staff estimated to be more numerous than the US Department of Homeland Security, the NSA, the CIA, and the FBI combined, Russia’s civil and military intelligence services are particularly strong in human intelligence, which sets them apart from most Western counterparts.

Propaganda is part of the strategy to influence Western perceptions. Aside from the work of intelligence, the Kremlin provides considerable funds to its media arsenal. Besides various news agencies and local media, it sponsors the world-wide TV network RT (earlier ‘Russia Today’). It is Russia’s weapon in global information warfare, according to its executive editor. In 2013, its budget was over US$ 300 million. Drawing mostly on Western TV anchors, RT has been giving Russia’s view of current events and history, often spawning conspiracy theories against the US, alongside coverage of social issues and negative aspects of Western societies. As Hannes Adomeit noted, “Evil America Today” (EAT) might therefore be a better name for this channel. It has been quite successful, being among the top three news channels in the UK and the US. Likely by using techniques of search engine optimization, RT also became the dominant news channel on YouTube.

Challenging the West

Russia has a pragmatic and unconstrained approach to using its instruments, frequently combining coercion and ‘soft power’. The Kremlin clearly believes that this hard-nosed pursuit of power politics against the West will ultimately be successful, if it chooses its targets wisely. This can best be demonstrated in three areas: Russia’s policy in the post-Soviet space, its quest for influence in the EU, and its dealings with the US relationship.

Ukraine and Georgia: locking the West out

The post-Soviet space is key for Russia’s renewed imperial identity and for domestic stability. Various cultural, economic, and social ties between Russia and its neighbours, often weak nations, complicate the emergence of truly independent nation states, and the Kremlin has chosen to exploit this fact. To secure regime survival, it prefers to have weak nations on its borders. Meanwhile, strong nation states and competitive economies look like threats to the own system out of a Kremlin window.

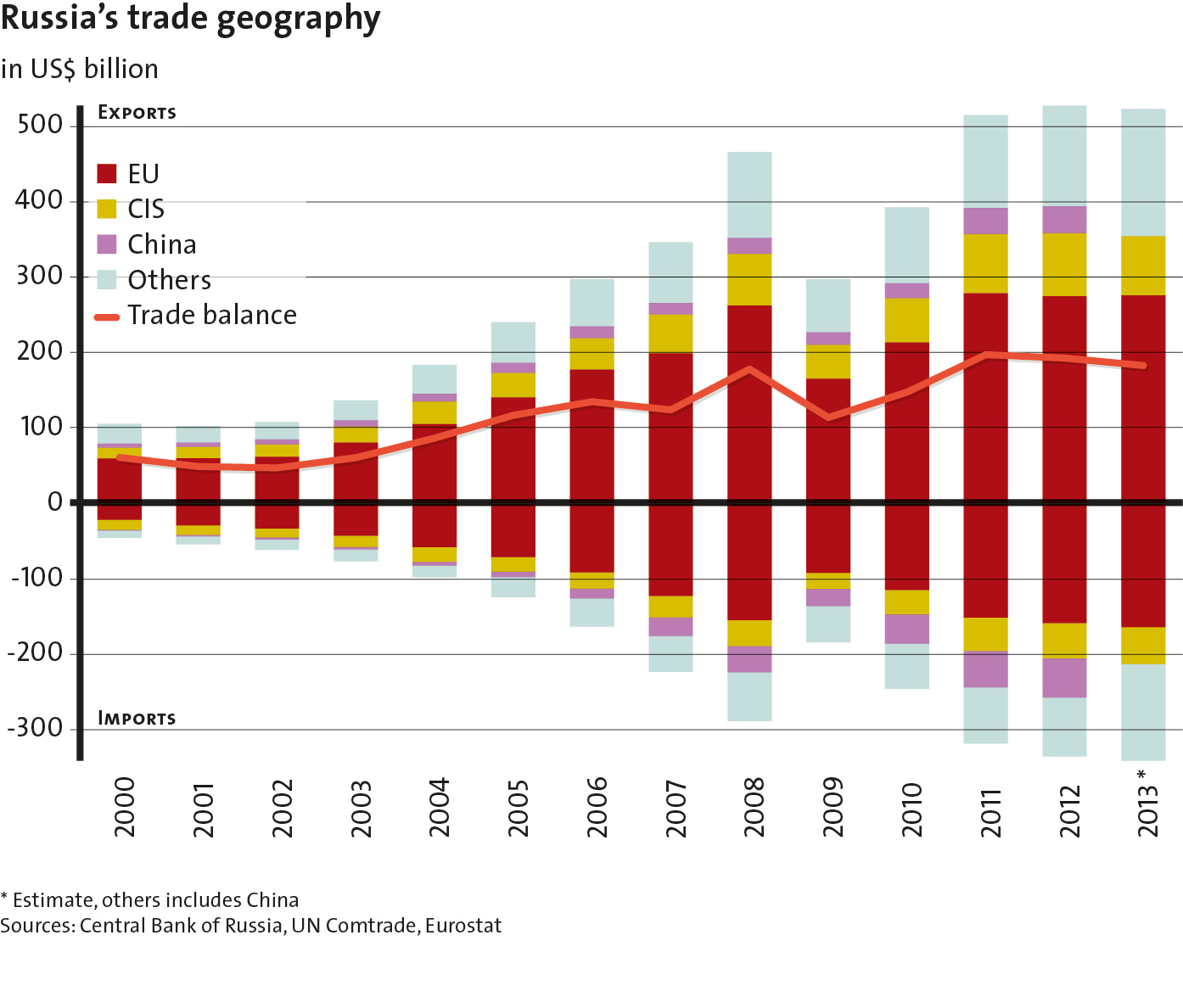

Russia's Trade Structure

President Putin considers it especially vital that Ukraine develops along similar lines as Russia. This is central for his hold on power, as both countries are connected by close cultural ties. Kyiv takes a special place in Russia’s history as the birthplace of orthodox Rus. This makes it easy for the Kremlin to claim that Ukrainians are ‘Little Russians’, and are in fact of the same blood. Indeed, many Russians do not see Ukraine as a foreign country. Thus, Ukraine adopting a different trajectory from Russia would bode ill for the Kremlin, as Russians would both see it as a foreign policy defeat and might ask questions about the legitimacy of the Russian regime.

When Ukraine’s President Viktor Yanukovych was about to sign a free trade and partnership agreement with the EU, Russia used a combination of coercion and inducements to hammer the point home that Ukraine had to choose between Russia and the EU. Russia used its traditional tools of selective import bans, and went on to severely complicate customs procedures for all Ukrainian goods as a “preventative measure”. It also threatened to cancel orders for Ukrainian heavy industry if the deal with the EU were to go ahead. This hit the already foundering Ukrainian economy.

At the same time, Putin was ready to hand out a large amount of financial and non-monetary benefits to Yanukovych. Not only did he pledge to invest US$ 15 billion in Ukraine’s bonds, but he also significantly lowered the gas price for Ukraine at a price tag of US$ 4 – 5 billion annually. In view of this, Yanukovych agreed to deepen economic cooperation and to shun the EU. But he also agreed to be taken on a very short leash, as gas price reductions have to be confirmed every quarter, while the buying of bonds can be withheld at any time. In effect, Yanukovych allowed Putin to become the guarantor of his reign.

Everything thus went according to Putin’s plan, barring the human factor. The ‘Euromaidan’, mass protests for accountable governance and national dignity in Kyiv and the west of Ukraine turned into a major irritant for the Kremlin. It repeatedly encouraged Yanukovych to crack down on what it sees as “terrorists” and “extremists”. Yet Yanukovych’s periodic and ever more brutal crackdowns eventually took a high death toll. Yanukovych had to agree to an end to his reign. As his personal security abandoned him, he fled Ukraine for Russia. The opposition formed a new government and called early presidential elections. Yet its authority remains precarious.

Supporting Yanukovych, Putin had bet on the wrong horse. To cover up this failure and to regain leverage over Kyiv, Russia even compromised Ukraine’s territorial integrity. In violation of the security assurances given to Ukraine in the 1994 Budapest memorandum, Russia supported “self-defence forces” in Crimea and vowed to use all available means to protect “compatriots” all over Ukraine. This soon led to Russia’s de-facto control over the peninsula, sparking off the biggest crisis in postCold War Europe. A break-up of the country, while being a worst-case scenario, is a real danger. The ultimate outcome of Ukraine’s revolution is thus very much in the balance and depends on the Western reaction.

Five years before the crisis in Ukraine escalated, Russia had already sent a clear and decisive signal to the West that his sphere of influence must not be infringed upon. The “short, victorious war” with Georgia in 2008 demonstrated the Kremlin’s willingness to use conventional military force to achieve broader foreign policy goals. The goal was to limit the ability of neighbouring countries to choose their foreign policy orientation. The Kremlin chose to once and for all stop further NATO enlargement in the post-Soviet space.

After provocations involving Russian troops, Georgia had attacked Tskhinvali, the ‘capital’ of its breakaway republic of South Ossetia. Russia intervened, beat back the Georgian attack, yet ventured deep into Georgian territory and also sent troops to the breakaway republic of Abkhazia, about 250 kilometres away from the original battle. Western powers were shocked, but did not sanction Russia or step in to help Georgia. French President Nicolas Sarkozy eventually brokered a ceasefire agreement, which led to an end of hostilities, but was never fully honoured by Russia.

Officially, the Kremlin justified its incursion by the “genocide” against South Ossetia, yet comments by Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and other officials before and after the war drove the point home that such “consequences for geopolitical stability” were to be reckoned with if NATO were to be further enlarged. In justifying the war by a responsibility to protect citizens abroad, Russia also went against its own foreign policy concept, which stresses strict noninterference in internal affairs and state sovereignty. Somewhat cynically, the Kremlin also tried to use the war as an argument for a new European security treaty, designed to sidestep NATO in Europe.

Russia and the EU: divide et impera

While Russia aims to lock the West out of its strategic glacis, it tries to drive the US out of Europe. Weakening NATO and US influence has long been the Kremlin’s key goal visà-vis the EU. From the start of his reign, Putin has made it clear that he thought of the US presence in Europe as an artificial one, a remnant of the Cold War. The commitment of the US to its European NATO allies helps to equalize power relations across the continent. It strengthens the sovereignty of and gives considerable voice to small nations, while keeping the power of big nations in check. Pushing the Americans out is thus supposed to re-establish a European concert of powers. The EU would cease to be the exclusive forum for rule-setting in Europe, but would be superseded by an overarching agreement between EU member states and Russia, backed up by a coalition of European great powers, including Russia. At the least, Russia demands an institutional forum to decide on European security issues that would side-track NATO in Europe. Given the low profile of many European states in military affairs this would give Moscow a loud voice. It would also presuppose that Europeans accept the status quo in Russia and view the current regime as legitimate. The Kremlin could then feel safe.

Energy is the keyword capturing the ambivalent relationship. It ties Russia and the EU together, as the EU is the main market for Russia’s hydrocarbons, while Russia is the EU’s main energy provider. Yet this renders energy a foreign policy tool as well. The Kremlin has played off different member states against each other and against Brussels, advancing its projects to lock in markets. It has also confronted the EU’s diversification plans, for example in the Caucasus and Central Asia. The message was that the EU should be happy that it is receiving Russian natural resources at all and should not complain about the conditions. This met with growing resistance from Brussels, which tried both to limit Moscow’s clout on the EU energy market and went on the lookout for alternative supplies. But whereas Moscow had to recognize that gas is still not so scarce that market forces can be suppressed, the EU’s quest for diversification has not been hugely successful either. And the EU’s reserves are dwindling. The Kremlin could thus underline the claim that accepting the status quo in Russia is a precondition for EU energy security, which only Russia can guarantee.

Naturally, Russia’s ambitions to revise the post-Cold War order in the post-Soviet space are of concern for the EU. The knowledge of Russia’s sizable and growing military potential has elevated Russia’s clout, as the EU cannot guarantee the security of its neighbours against Russia. These perceptions have been re-inforced by cyberthreats against the Baltics and by military muscle-flexing at the EU’s borders. In line with Russia’s military modernization efforts, this has given credence to the claim that Russia needs to receive a seat at the EU table, even if it has muscled itself into this position.

Beyond hard power politics, the Kremlin has also worked hard to raise the acceptability of its regime in Europe. This includes raising attraction by providing resources committed to information warfare, while closing down Russia for Western influence. The Kremlin’s funding of international media is key, as is skilful manipulation of online communities. Another element is drawing on pre-existing postCommunist networks and establishing new relations with power brokers in politics and business. More recently, Putin’s conservative turn has increased the Kremlin’s influence among the European New Right. In France, Marine Le Pen has detected common values with the Kremlin, stretching from opposition to gay rights to “economic patriotism”. East of the Rhine, the economically liberal, yet culturally nationalist ‘Alternative for Germany’ also revealed understanding for Russia’s continuing drive to dominate Ukraine.

Russia's Gas Export Infrastructure

Russia’s growing assertiveness towards the EU has had an ambivalent effect. On the one hand, it has raised calls for greater cooperation and acquiescence to Russia. Yet on the other hand, European elites have been increasingly estranged by Moscow’s behaviour, thereby complicating Moscow’s divide et impera approach. But a common strategy on how to deal with Russia has not yet emerged.

Russia and the US: vying for global status

Whereas Russia’s goal in Europe has been to push the US out, on the global level Russia mainly sought recognition of its great power status. Real opposition to US policy has been modest and fairly defensive, where core interests of the Kremlin have not been touched. As the US scaled down its global ambitions under President Barack Obama, opposing the US became a low-cost opportunity. While Washington did not punish these moves, they brought domestic dividends. And even in more substantial fields, Russia was able to score some remarkable successes.

In launching the ‘reset’ policy with Russia in 2009, Obama wanted to get rid of the legacy of President George W. Bush’s presidency and lead relations to a new level. Hopes were high that a fresh start would be possible with President Dmitri Medvedev, but he proved to be not much more than a fill-in for Putin. And the Kremlin knew that the driver of the reset was not US strength, but rather Washington’s desire to offload problems in order to turn towards more important issues. The ‘New START’ treaty on nuclear reductions was the main achievement. Yet this treaty mainly reaffirmed Russia’s status as a nuclear power, while its ratification was made contingent on US restraint on missile defence.

Once Putin was back as president, he pursued a more assertive policy towards US presence in Europe. The issue of NATO’s missile defence system again moved to the forefront, even though Washington had opted for a less advanced system. While the system cannot present a threat to Russia’s nuclear second-strike capability, Putin fiercely opposes the system in order to strengthen domestic legitimacy and to avoid a stronger anchoring of the US in Europe. To increase the stakes, the Kremlin is even ready to let the whole architecture of arms control unravel. After exiting the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe in 2007, it successfully tested a new ballistic missile in 2013 that likely violated the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Of course, the Kremlin identified the US and Western countries as the trigger for these moves.

After the reset failed, it was and is the war in Syria that provided Russia with an opportunity to take centre stage on a global level. Not only was Russia present and leading at every important diplomatic initiative and negotiations, but Russia even outmanoeuvred the US and was able to protect its ally Bashar al-Assad. By underwriting the ban on chemical weapons the Kremlin could position itself as a ‘good citizen’, while the killing continued. Moscow could also exploit the situation to show the deleterious consequences of “interference in internal affairs” – meaning the Western focus on humanitarian issues.

Russia acted cynically and played its cards realistically. Claiming to fulfil previously concluded contracts, Russia continued to supply arms and military advice to Assad’s forces. At the same time, Gulf States, and later the West, were quick to take sides against Assad, supporting and even arming rebel fighters. When Obama dithered to defend his ‘red lines’ considering the use of chemical weapons, Putin seized the opportunity and pressed Assad to abandon its chemical weapons potential. Putin got Assad on board and scored a diplomatic success, while the killing did not stop.

By contrast, the US had badly miscalculated. By abandoning Assad early on, it put all its chips on the opposition, knowing that the stakes were high. When this failed, it did not commit to a military intervention. Russia would not have granted legitimacy to such an operation in the UN Security Council, but neither did it do so in Kosovo or Iraq. As the West did not have the will to fulfil the ‘Responsibility to Protect’, Russia’s position of “non-interference” triumphed. The West helped to fan a major bloodshed, yet it lost credibility in its wake.

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden has become only the latest addition to these US foreign policy setbacks. For Putin, Snowden came in handy as a propaganda tool to strengthen legitimacy at home and to win new friends abroad. Putin masqueraded as nobleman at first – asking Mr. Snowden for assurances that he would do no harm to his US “partner” – but then went on to grant asylum nonetheless. Yet the fact that the Kremlin could emerge as the world’s chief whistle-blower exposes a deeper problem for the West: The ‘Global War on Terror’ has taken a toll on the very values that the West stands for. As policy-makers on this or that side of the Atlantic did not seek approval for their dealings, the lack of explicit consent enabled the Kremlin to play the Snowden card against the US.

Accepting the challenge

Russia is back on the world stage, and it is not converging with, but actively opposing the West. Contrary to what the West hoped for in the 1990s, Russia has not embarked on the path of becoming a ‘normal’ democratic nation state. Rather, Moscow’s imperial ambitions have been revamped. Russia is consciously implementing an anti-Western foreign policy out of domestic necessity. Locking the West out of Ukraine and Georgia, pushing the US out of Europe, and regaining the lost diplomatic equality with Washington are the three core agenda items. Although Russia has tried to develop soft power instruments, its policy is still focused on hard power and falls short when dealing with societal challenges.

Russia’s agenda has been chosen wisely, as it avoids overstretch. Russia is not able to act forcefully in East Asia or in the Americas, but it is strong in Europe. Hence, the West cannot wish away and ignore Putin’s Russia anymore. Neither can it project its own wishes and images on Russia, hoping that they may come true. In the mid-term, this Russia is here to stay, and the West will have to learn how to cope with it and factor it into its own strategies.

In the longer term, the bite of Putin’s instruments and the basis of Putin’s power politics may well founder. Economic performance is still Putin’s Achilles heel, and energy revenues may not be a panacea for all woes. In the event of dismal economic performance, Putin might be forced to fundamentally change his foreign policy. What is more, Putinism’s strong personalization will complicate the eventual choice of a successor when Vladimir Putin leaves office. Last but not least, Russia’s eastern neighbours are rising, and the anti-Western agenda of the Kremlin alone will fall short in meeting these new challenges.

However, for the years to come, the West will have to accept Putin’s Russia as a policy challenge and devise a strategy to deal with it, while preserving its identity and values. Just continuing to ignore the Kremlin’s foreign policy or hoping it will change sooner or later is a non-strategy and has reached an obvious dead end.