1968–1973: Co-determination seen as a problem

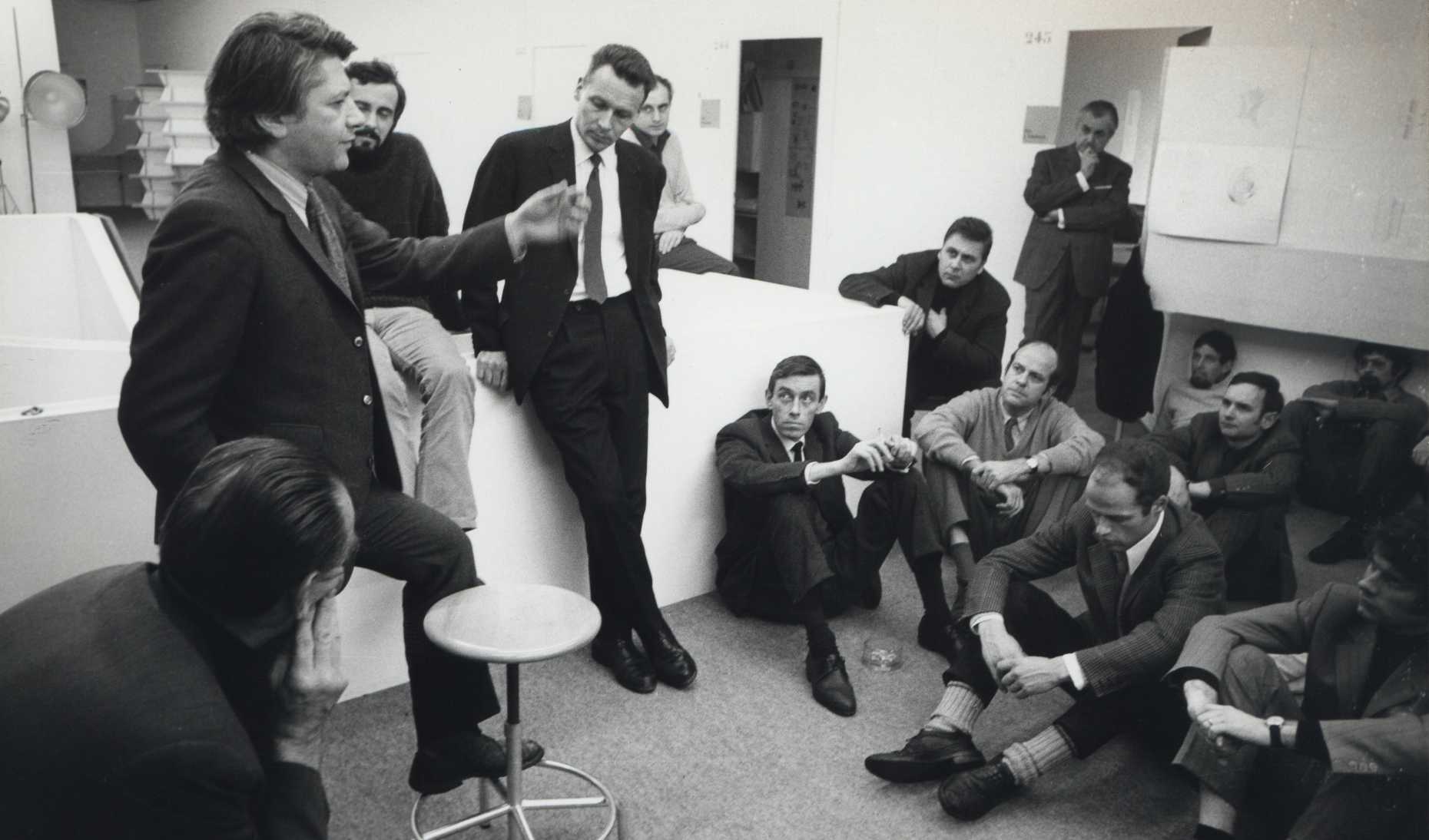

Between 1968 and 1973, the crisis about the future orientation, growth and structure of ETH affected it on various levels. New forms of education and new course contents were just as much the subject of debate as were new rules and regulations.

Key dates for this period:

Reform backlog caused by student referendum

In 1968, the Swiss Federal Parliament passed a new Federal Institutes of Technology Act to take account of the takeover of the Ecole Polytechnique in Lausanne by the federal state. However, since the text of the Act largely failed to address the question of co-determination, the students called for a referendum. In June 1969 the proposal was rejected at the ballot box.

This decision by the people had numerous consequences for ETH. It was a reflection of the reform backlog which the President of the Swiss Science Council, Max Imboden, had already diagnosed in 1964 as a "Swiss malaise". Even the launching of the referendum itself by the students was a direct affront to the political-academic establishment of the day. The victory by the student body showed that "ETH" by no means shared the views of its Executive Board. Instead, it had become clear that co-determination was a problem. Furthermore, the surprise rejection of the Act meant that a whole raft of transitional regulations was now needed for the federal universities to continue to negotiate. Federal policy on science became more diverse and ceased to be almost entirely focused on ETH as it had been before.

Reorientation in difficult staffing conditions

This sudden crisis was followed by a reorientation process that was marked by long and heated debate and also soon had to be carried out in extremely difficult staffing conditions. This was because the Swiss Federal Council had imposed a general halt to recruitment in the early 1970s, meaning that structural problems could only be resolved by a reallocation of resources, not by growth.