Biosensors in the pharmaceutical industry

A Nobel prizewinning idea bears entrepreneurial fruit: an ETH Pioneer Fellow is applying knowledge about G-protein-coupled receptors to market a novel process for testing drugs.

Few people will have heard of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) until fairly recently, when Brian Kobilka and Robert Lefkowitz won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work on them in 2012. The prize recognised their achievement in illuminating the fundamental functions of GPCRs – an unwieldy moniker that is nearly impossible to remember for anyone who doesn’t work with these receptors constantly.

Then in mid-April 2016, ETH Pioneer Fellow and former ETH doctoral student Martin Ostermaier joined with Aurélien Rizk and Luca Zenone to found a company based on this Nobel prizewinning work. The three up-and-coming researchers called their company external pageInterAx Biotechcall_made; they have now officially established it and registered it as a spin-off of both the ETH Zurich and Paul Scherrer Institute.

Major implications for pharmaceutical research

People outside the field might wonder at how quickly this basic research has moved into practice, but Ostermaier says it’s no surprise: “Even before I began working on my doctorate at ETH Zurich, I knew how important GPCRs would be for drug research.” One third of today’s medications target these receptors, which are found in the outer layers (membranes) of cells in the human body. These drugs range from beta-blockers for treating high blood pressure to antipsychotics for mental illnesses. Science has identified about 800 different GPCRs, although just 370 of them are suitable as a docking site for medications; thus far only one sixth of these can be used for pharmacological purposes.

Often what happens is that pharmaceutical researchers will have identified a GPCR they wish to target, but lack the methods for accurately testing whether their drug works as planned, explains Ostermaier. It would be a huge step forward for all GPCR-medication research if a method were found that made it possible to find medications for other usable GPCRs, or improve medications for the GPCRs already targeted. “This is precisely the issue we are working to resolve,” Ostermaier says.

Customised biosensors

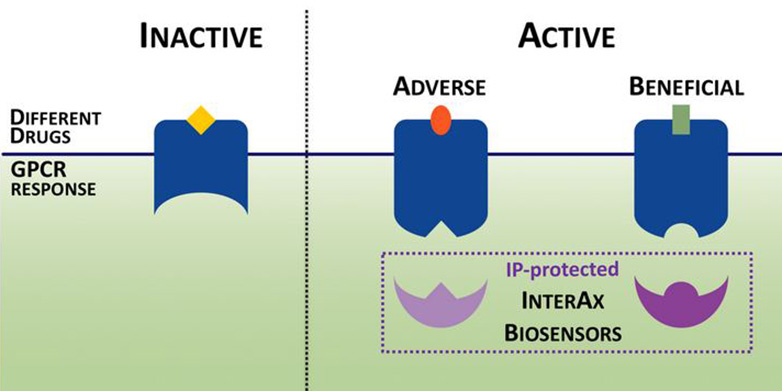

InterAx is developing new kinds of biosensors that increase the speed and accuracy of testing if and how a particular drug affects a certain receptor. The biosensors work based on the fact that a receptor’s state changes as soon as a drug docks with it. Each state triggers a signal path that has a specific effect in the cell. However, because a GPCR can adopt various states, it can send different signals.

The young entrepreneurs now aim to deploy their specific biosensors to detect which GPCR states are triggered by the drug being tested. Because the biosensor, a customised protein, binds only to one specific state, the scientists can determine not only if the drug has initiated a reaction in the target GPCR but also whether that reaction was desired or unfavourable. And as the bond between biosensor and receptor is quite stable, it is possible to investigate the drug’s effect on the GPCR, and to do it better, more simply, and with quantitative results.

But InterAx supplies more than biosensors; the company also provides customised software that processes the data produced by the tests and quantitatively evaluates it. “Customers benefit from a complete package,” says Ostermaier. The goal is to eventually offer plug-and-play applications.

Latest addition to the ETH spin-off family

InterAx was officially founded in mid-April, but its founders had already invested a considerable amount of time and effort in building it up. It was for this company that Ostermaier received his Pioneer Fellowship from ETH Zurich. “I was thrilled about getting this support. The funds have allowed me to keep pursuing my ideas, even after completing my doctorate,” says Ostermaier. InterAx was launched at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Villigen, where Ostermaier works with external pageGebhard Schertlercall_made. A full professor at ETH Zurich and a renowned GPCR expert, Schertler provided the three young entrepreneurs with plenty of support and encouragement as they were setting up InterAx.

Ostermaier and his two partners received further funds in February as winners in the Venture Kick competition. In this contest for start-up funding, their business idea won through to the third and final stage, netting them CHF 130,000 in seed capital.

Massive expansion planned over the next six years

These funds are by no means enough to grow the company. To further develop its ideas, InterAx is looking for other investors willing to contribute a total of CHF 3.5 million. Ostermaier and his colleagues wish to put that money towards building their own infrastructure and rapidly extending the technology. These capital injections will also determine how quickly the company can hire new people; they are especially interested in recruiting cellular biologists and biophysicists.

InterAx plans to begin marketing its first biosensor before the year is out. In six years, the founders expect to expand their product range to include 80 different sensors, representing sales proceeds somewhere around 50 million.

“This is just a forecast,” says Ostermaier. “For it to actually become a reality depends on many things over which we have no control.”