Some like it even hotter

Scientists in Iceland have drilled into a reservoir of extremely hot water that has the potential to greatly expand geothermal electricity output. Now ETH geoscientists have for the first time been able to produce a realistic simulation of how such reservoirs are created. They predict that these natural phenomena are widespread in volcanic areas.

Iceland has been using geothermal energy to generate electricity for decades. To do this, engineers drill down one to two kilometres to tap underground sources of hot water that can reach temperatures of between 250 and 350 degrees. These hot water reservoirs arise when groundwater is heated by magma bodies trapped in the rock.

In 2008, while hunting for even hotter geothermal reservoirs that can provide more energy, Icelandic researchers working on the Iceland Deep Drilling Project (IDDP) began drilling a five-kilometre borehole on the Krafla lava field. However, the drill got stuck just two kilometres down. They ran into the same problem with a second borehole. Both times, their drilling head came up against what geologists call a magmatic intrusion: a rising mass of viscous magma that remains stuck in the bedrock rather than breaking out at the surface.

Drilling into a reservoir of supercritical water.

Directly above the magma chamber, the researchers discovered a hitherto unique geothermal reservoir of water: one in which temperatures reached 450 degrees, a state which scientists refer to as supercritical.

Water becomes supercritical when heated above 374 degrees, from which point it starts behaving like a mixture of the gas and liquid phases. The two phases become inseparable and indistinguishable, resulting in a fluid that can be as dense as a liquid but at the same time flow as easily as a gas.

Water that has been heated by the magmatic intrusion to a supercritical temperature contains enough thermal energy for a single borehole to provide 35 megawatts of electrical capacity. In comparison, today’s standard geothermal boreholes have a capacity of 3 to 5 megawatts; a whole series of boreholes must be connected in a circuit to form a power station with a capacity of 50 to 100 megawatts. Given that each borehole costs several million dollars, it’s easy to understand the attraction of supercritical geothermal water.

In 2011, two years after this unusual energy source was discovered, the IDDP consortium began conducting tests at the borehole. They made a lot of new discoveries, but they were unable to shed any light on how the reservoir had come to be. Was it a freak of nature, or might such reservoirs be more widespread than people had assumed?

A computer model gives a glimpse underground

Three ETH geoscientists decided to simulate this unusual geothermal system using a new computer model – and now they understand how it occurs, under what conditions it can arise, and where to look for other such systems. Their results and the associated modelling have just been published in Nature Communications.

“The simulations offer a realistic representation of this reservoir’s behaviour, even though we kept the model as simple as possible and built in only a few parameters,” says Thomas Driesner, a senior lecturer at ETH Zurich’s Institute of Geochemistry and Petrology, adding that the most satisfying thing about the simulations was that they reproduced what the Icelandic IDDP researchers had observed at the borehole.

Rock permeability is decisive

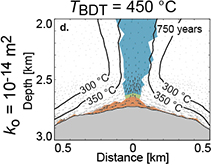

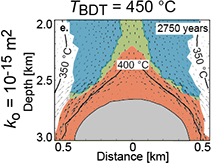

At 1,000 degrees, the magmatic intrusion is absolutely impermeable to water. Driesner’s doctoral student Samuel Scott was able to use the simulations to show that a decisive factor in the formation of such a geothermal reservoir is the permeability of the surrounding rock. If it is highly permeable, then water can rise through it without difficulty – transporting heat away from the intrusion more effectively and hence cooling the magma more quickly. But if the surrounding rock is only slightly permeable, the water remains trapped above the intrusion, which can then heat it up to beyond its critical point. What’s more, given the “poor” heat transfer, the magma chamber stays hot for longer.

Basalt is the ideal “incubator”

The permeability of the rock in the direct vicinity of the magma is key. Here, where temperatures and pressures are high, the mode of deformation of the host rock shifts from brittle fracturing to plastic flow, causing cracks and fissures through which water might flow to close up. The temperature at which this occurs will determine how hot the water can get. Different types of rock begin to exhibit plasticity at different temperatures. While basalt, a typical volcanic rock, becomes plastic and impermeable at around 500 to 800 degrees, this transformation occurs in more silicon-rich granite at just 350 degrees.

In other words, if the rock surrounding a magma intrusion is basaltic, then there’s a good chance that such a geothermal reservoir might form. “That’s why we expect this type of heat reservoir to be more common than previously thought in volcanic areas such as Iceland, New Zealand or Japan,” conclude the ETH researchers based on their modelling.

Model helps to find reservoirs

Their model illustrates which interactions are necessary between various geological factors –permeability of the host rock and the temperature at which that rock becomes plastic, and the depth of the intrusion – for ideal conditions to arise for reservoir formation. This knowledge helps to narrow the search for such reservoirs of extremely hot water.

“The model gives us some idea of the criteria by which these zones develop – and how to recognise them,” Driesner explains, adding that while natural situations are certainly more complex, the model is nonetheless a good tool and will make it easier to find this type of energy source.

Now the researchers are also looking to expand this method. As part of a Sinergia project with funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), they want to work closely with geophysicists to find out whether these reservoirs can also be detected using seismic techniques.

Further drilling is planned

The ETH research team is involved in international collaboration that brings researchers and specialists from Switzerland, New Zealand, Australia, the USA and Iceland together to drive the development of geothermal techniques. In Switzerland, insights gained from this collaboration are also flowing into national initiatives. Among them is SCCER-SoE, the ETH-led Swiss Competence Centre for Energy Research – Supply of Electricity, where for instance the simulation methods used are being adapted to suit the requirements of geothermal projects in (non-volcanic) Swiss subsoils.

Iceland lies on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the zone along which the Eurasian and American continents are drifting apart. At some points in the zone below Iceland, the earth’s crust is just six kilometres thick, which means magma can easily reach the surface and volcanism is widespread.

Driesner suspects the Icelandic part of the ridge is home to further magmatic intrusions that might be surrounded by reservoirs of supercritical water and hence be of interest to the energy industry. The Icelandic researchers are about to drill a second test borehole on the Reykjanes Peninsula. But according to Driesner, this is a site at which seawater seeps into the subsoil, which completely changes the properties of supercritical water and means their model will be only partially correct for the conditions pertaining there. That’s why, for the next chapter of his doctoral thesis, Samuel Scott has already begun to adapt the model so it factors in the saltwater.

Reference

Scott S, Driesner T, Weis P. Geologic control on supercritical geothermal resources above magmatic intrusions. Nature Communications 2015. DOI external page10.1038/ncomms8837call_made