New Security Arc in Mideast

3 Jan 2017

By Christina Lin for Institut für Strategie- Politik- Sicherheits- und Wirtschaftsberatung (ISPSW)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageInstitut für Strategie- Politik- Sicherheits- und Wirtschaftsberatung (ISPSW)call_made in December 2016.

Abstract

With the recent Saudi-Egypt rift over Syria, and Cairo's pivot towards Russia and Iran, a new security arc is emerging in the Middle East. The arc consists of Iran, Iraq, Syria, backed by Russia and China, with Egypt, Turkey and Jordan slowly aligning with the arc to counter Salafi terrorism. In contrast, the US-led coalition with Saudi Arabia and Qatar are focused on supporting Salafi jihadists to conduct regime change. As Egypt, a large Sunni Arab country pivots to Eurasia, Riyadh's argument that the Syrian war is a sectarian conflict is no longer valid, and presents an opportunity for realignment in the Middle East with China as a crucial new player.

Analysis

With so much focus on the battle in Aleppo, there has been little attention on the Saudi-Egypt rift in the media. And along with this western blind spot is China’s rising influence as a crucial player in Egypt and the Middle East.

Saudi-Egypt spat over Syria

The Riyadh-Cairo spat began in April 2016, when Egypt’s Sisi agreed to cede territorial integrity over two of its islands, in exchange for a series of lucrative contracts and promise of Riyadh’s diplomatic support. The two islands, Tiran and Sanafir, are strategically located at the southern entry of the Gulf of Aqaba, where both Israel and Jordan maintain important ports.

This subsequently unleashed outrage among the Egyptian population, with former presidential hopeful (2014) Hamdeen Sabahi denouncing it violated Egyptian Constitution to cede territory, and attacks on Sisi’s legitimacy for subjugating the once proud Arab nation of Egypt to the Saudis. In June, the Egyptian court nullified the deal, only to be overturned in September, with the possibility of being appealed once more. Currently it is still unclear whether the two islands will remain with Egypt or be annexed by Saudi Arabia, punctuating what Issandr El Amrani1 from the International Crisis Group describes as a relationship “based on a kind of asymmetric passive-aggressive perpetual renegotiation.”

The rift widened in October. Following the September discussion between Iran and Egypt’s foreign ministers on the sidelines of the UN General assembly, Tehran invited Egypt to join international talks over Syria, and days later Cairo voted for Russia’s UN Security Council resolution that backed the Syrian government. In turn, this prompted Riyadh to punish Cairo’s perceived intransigence, by cutting off 700,000 tons of refined oil products as part of $23 billion deal signed earlier this year.

Whatever happened to the Saudi-Egyptian “Camp of Stability”?

In the past, Cairo enjoyed good ties with Riyadh. However, after King Abdullah passed on and was replaced by King Salman who is friendlier towards the Muslim Brotherhood – which Egypt considers a terrorist group – Sisi began to distance Egypt from the pro-Islamist axis of Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar in the Middle East. The Obama administration’s support for the Brotherhood further fuels Egypt’s sense of betrayal, compounded by GOP threats to cut off aid over Sisi’s anti-democratic legislations, and austere IMF conditions of rolling back energy subsidies that could further destabilize Egypt in midst of waves of terrorist attacks.

Unlike Washington, Sisi recognizes that foreign support for the Muslim Brotherhood and increasing terrorism in Sinai threaten the Suez Canal’s stability, which is inextricably tied to Egypt’s own economic development and future. According to military sources, Morsi’s collaboration with Sinai jihadi groups was a source of their disagreement and eventual fallout. Indeed, with $5 billion a year in revenues from the Canal, it is a vital source of hard currency for a country that has suffered a slump in tourism and foreign investment since 2011.

Moreover, Sisi sees Assad as a secular bulwark against Islamic extremism in the Levant. If Assad falls, Lebanon and Jordan would be next, and Egypt does not want to end up like Libya with the Brotherhood and other Islamists carving up the country. In response, Cairo is turning towards Russia and Iran, and forming what former Oxford University scholar Sharmine Narwani describes as a new “Security Arc” in midst of Mideast terror.

Realignment in the Middle East

With Egypt pivoting towards Syria and Iran, this now further solidifies the Eurasian coalition of Syria, Iran, Russia, China and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) where Egypt is an aspirant partner. It also highlights the divide between the Eurasian coalition to counter Salafi terrorism, and the current US/Turkey/Saudi/Qatar coalition to support Salafi jihadists2 for regime change.

More importantly, with Egypt as a large Sunni Arab nation aligning with the Syrian government and the Eurasian bloc, Riyadh’s argument that this is a sectarian conflict is no longer valid. Indeed, the more the US/Saudi nexus bolster Wahahbis, the more this repels moderate Sunni Muslim states and push Asian states to coalesce with Iran as a natural ally.

Which of course puts Israel in a tough spot. Having chosen to adopt the posture of siding with the Saudis to remove the Assad government at all cost, Jerusalem is increasingly isolated in the Levant as the map shows. As Washington steadily retrenches from the region, and unlikelihood Trump can dismantle a multilateral nuclear deal enshrined in the UN, what recourses does Israel have to safeguard its security?

Enter the dragon in the Great Sea.

Given that various great powers have vested interest in the survival of the secular Syrian government, Jerusalem may perhaps follow in Turkey and Egypt’s footsteps to pivot east towards Eurasian powers.

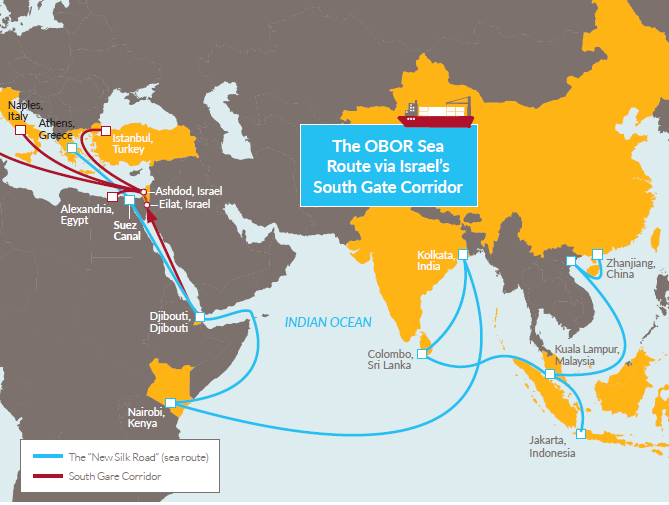

Already Turkey will chair3 the SCO Energy Club in 2017, and have signed a series of deals in November to cooperate on China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiatives. Egypt is also rapidly upgrading ties with China to help stabilize its economy. As the world’s largest trading state, soon to be largest economy, and EU as its top export market, China’s trade and economic well-being depends on the Suez Canal as an important lifeline.

To that end China has helped build the Suez Canal Economic Zone, and now has plans for a $45 billion4 business capital east of Cairo as well as investing $15 billion in electricity, transport and infrastructure projects. Some of these projects will be funded by China’s Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) where Cairo is a founding member.

As China gains more influence with Egypt, Syria, and Iran, it could perhaps play a role in tempering Israel’s security concerns.

China’s role in improving Israel-Egypt ties

Given both China and Russia’s massive injection of military and economic investments to stabilize the Middle East, they clearly have no interest in having Iran attack Israel to further destabilize the Levant. Nor would Beijing want Israel to attack Iran, a strategic hub on the OBOR linking the Middle East, Central and South Asia.

As such Moscow and Beijing can exert influence over Tehran and help mitigate tensions with Jerusalem. Furthermore, China can improve Israel’s ties with Egypt and Jordan by investing in Jerusalem as an essential part of the global trading ecosystem.

A recent BESA Center report5 highlights that the proposed Med-Red rail linking Eilat to Ashdod could provide opportunities for improving regional relationships. As a complement to the Suez Canal, and if extended to Jordan’s larger Aqaba Port, this could increase cargo traffic between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean and further link Israel’s economy with Jordan and Arab Gulf states.

An auxiliary cross-Israel natural gas pipeline between Eilat and Ashdod can also export gas from Israel’s Mediterranean fields to Asian markets such as China and India via the Red Sea.

With Egypt and Israel as key components of the OBOR’s southern trade corridor, increased economic cooperation can eventually be complemented by security cooperation and counter-terrorism between China, Israel and Egypt to help maintain regional stability. Beijing and Cairo have already conducted joint naval exercises in the Mediterranean, with plans to further upgrade military ties.

China’s rising influence in the Middle East could thus elevate Jerusalem and Cairo in Beijing’s strategic calculus6, help strengthen ties, and as Jean Michel Valantin of The Red Team Analysis Society argued, perhaps present a new status of Israel and Egypt as “integrated regional powers” in their own right of not merely seeking “protectors”, but now of seeking partners.

Notes

1 Nour Youssef and Diaa Hadid, “We Don’t Owe Anyone: Egypt Jousts With Its Chief Benefactor, Saudi Arabia”, New York Times, November 1, 2016, external pagehttp://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/02/world/middleeast/egypt-saudi-arabia.html?_r=0call_made; Rohollah Faghihi, “How Syria is pushing Egypt and Iran closer”, Al Monitor, October 18, 2016, external pagehttp://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/10/iran-egypt-relations-syria-assad-saudi.htmlcall_made; Ismail Numan Telci, “Sis’s gagmble: How Egypt’s turn toward Iran changes power in the region”, Middle East Eye, November 11, 2016, external pagehttp://www.middleeasteye.net/columns/sisi-s-risky-gamble-how-resetting-egyptian-foreign-policy-shifting-power-1818341258call_made

3 “Turkey to chair 2017 Energy Club of Shanghai Cooperation Organization”, Daily Sabah, November 23, 2016, external pagehttp://www.dailysabah.com/energy/2016/11/23/turkey-to-chair-2017-energy-club-of-shanghai-cooperation-organizationcall_made

4 Tamer El-Ghobashy and Esther Fung, “Soft Power: China Backs Egypt’s New $45 Billion Capital”, Wall Street Journal, May 3, 2016, external pagehttp://www.wsj.com/articles/big-chinese-developer-pushes-overseas-ambitions-with-egypt-project-1462267802call_made ; Zaynab El Bernoussi, “The Growing Influence of China in the Middle East”, Gulf News, December 11, 2016, external pagehttp://gulfnews.com/opinion/thinkers/the-growing-influence-of-china-in-the-middle-east-1.1943466call_made

5 Mordechai Chaziza, “The Red-Med Railway: New Opportunities for China, Israel, and the Middle East”, BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 385, December 11, 2015, external pagehttp://besacenter.org/perspectives-papers/385-chaziza-the-red-med-railway-new-opportunities-for-china-israel-and-the-middle-east/call_made

6 Niv Elis, “Israel, China, launch joint task force for expanding ties”, The Jerusalem Post, March 30, 2016, external pagehttp://www.jpost.com/Business/Israel-China-launch-joint-task-force-for-expanding-ties-395610call_made

About the Author

Dr Christina Lin is a Fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at SAIS-Johns Hopkins University and a research consultant for Jane’s Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Intelligence Centre at IHS Jane’s. She is the author of "The New Silk Road: China's Energy Strategy in the Greater Middle East" (The Washington Institute for Near East Policy), and a former director for China policy at the U.S. Department of Defense.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.