Twin glacier collapse in Tibet

Giant ice avalanches caused by catastrophic glacier failures are rare events. The collapse of two neighbouring glaciers within two months – as just witnessed in Tibet – was never seen before. The timely analysis of satellite images enabled scientists to issue a warning prior to the second collapse.

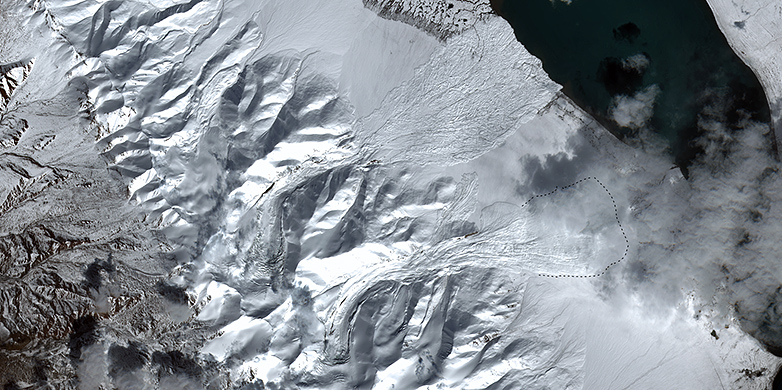

On 17 July 2016, a glacier near the Aru Co Lake in western Tibet collapsed completely. This caused an ice avalanche of roughly 65 million cubic meters in volume that killed nine herders and hundreds of animals [1]. The scale of this event surprised scientists and raised the question as to what could have caused a relatively flat glacier to lose contact to its base and to create such a giant avalanche. Up to this date, the only other known event of a similar scale was the “Kolka-Karmadon” ice avalanche in the Russian Caucasus on 20 September 2002, which killed more than 100 people [2]. Since such events are extraordinarily rare, after the collapse in July 2016, nobody ever imagined that just two months later an adjacent glacier would break down in a similar way.

Joint effort to analyse the cause

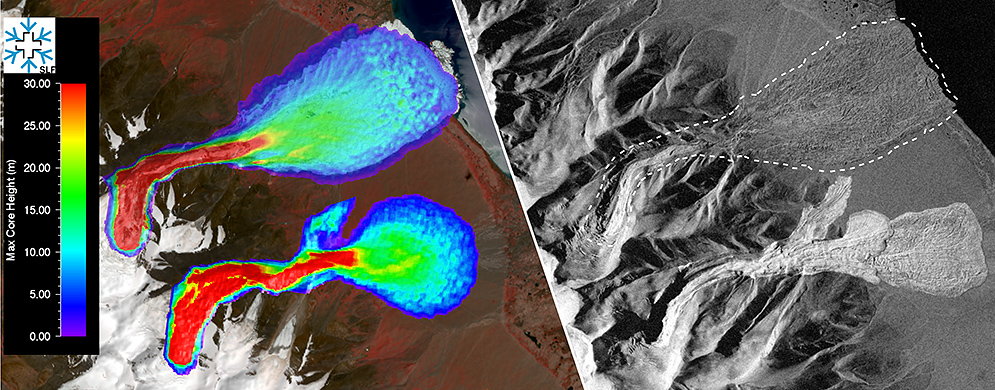

In order to understand the cause of the first giant ice avalanche on 17 July, we – an international team of scientists from ETH, SLF/WSL [3] and the scientific commission GAPHAZ [4] – began to investigate the glacier’s development prior to the collapse and to characterize the resulting avalanche. We did this through analysing a large number of visual and radar satellite images, in addition to running Rapid Mass Movements (RAMMS) computer simulations [5] to reproduce the event.

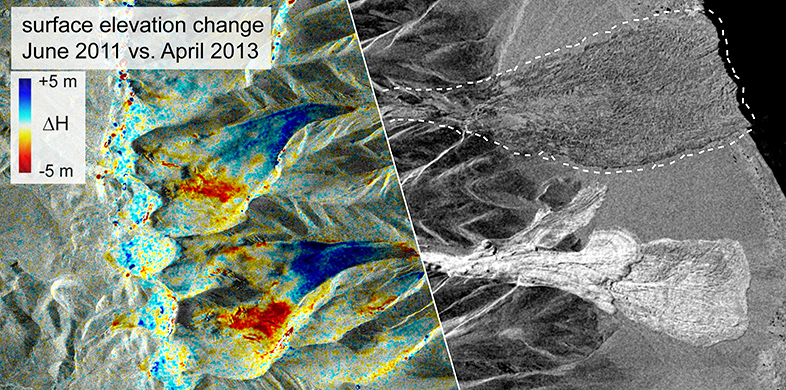

In the course of these retrospective investigations, we analysed glacier elevation changes retrieved from radar data acquired by TanDEM-X, a satellite mission led by the German Aerospace Center (DLR). These insights suggested that the glacier was in a so-called “surging” state prior to its collapse. A glacier surge is a temporary state of destabilisation, in which the excess ice mass from the upper part of the glacier is transported downstream at an unusually high rate. This caused the glacier to quickly gain velocity and advance by more than 200 meters within less than ten months. Glacier surges are common in some parts of the world, e.g. in the Karakoram or Alaska, but are rare in Tibet. However, these surges had until then not been known to cause catastrophic glacier failures.

An analysis of radar data from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) satellite Sentinel 1 showed that the surge started after snow melted in September 2015. However, the glacier "got stuck" in a narrow valley. This, we suggest, might have contributed to high amount of water accumulation under the glacier until it lubricated the glacier enough for the buttressing dam to break and, thus, causing the giant ice avalanche.

Adjacent glacier showed similar signs of surge

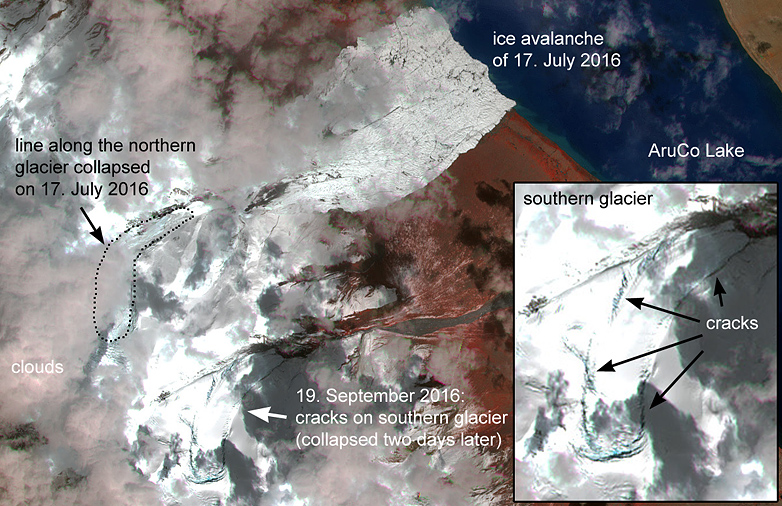

To our surprise, the analysis of surface elevation data from TanDEM-X revealed that also a neighbouring glacier with a very similar shape – the southern twin of the collapsed glacier – showed the characteristics of an ongoing surge. A few days later, a new satellite image acquired on 19 September 2016 by ESA’s satellite Sentinel 2 surprised us with obvious signs of ongoing dislocation, resulting in the opening of many new crevasses on the southern twin glacier. The crevasse pattern formed a several kilometres long line, almost identical to the line along its northern twin had failed, which alerted us to the possibility of an imminent second glacier collapse.

We discussed and modeled the risk of a new ice avalanche in collaboration with Yves Bühler (SLF) and Daniel Farinotti (VAW and WSL). Based on this information, SLF produced a hazard indication map for a possible second avalanche. Coordinated by GAPHAZ, the warning was rapidly passed to Chinese scientists, who then informed the local government. Only hours later, on 22 September 2016, the Chinese scientists reported that the second glacier had collapsed, making this event of a double glacier collapse absolutely unique in known history. To everyone’s relief, nobody was hurt by this avalanche, although the warning reached the local authorities a few hours after the second avalanche.

In search for explanation

All of the scientists involved were shocked when they received news of the second glacier collapse from their Tibetan colleagues. Together we are now starting careful investigations into the causes and triggers that could explain the mysterious collapse of the twin glaciers. Our particular focus is examining why two nearby glaciers failed at similar times in similar ways. This suggests that a possible combination of geological and topographic factors, meteorological conditions, and, very likely, recent climate evolution were involved.

Despite the possible connection of the twin glacier collapse with climate change, the fact that many different satellite observations could be analysed with a delay of only few hours marks a milestone in the progress of early warning capabilities and shows the importance of international collaborations.

Silvan Leinss co-authored this article with Daniel Farinotti.

Further information

[1] Nature news: external pageGiant, deadly ice slide baffles researcherscall_made

[2] Stephen G. Evans, et al, “external pageCatastrophic detachment and high-velocity long-runout flow of Kolka Glacier, Caucasus Mountains, Russia in 2002call_made”, Geomorphology, Vol. 105, Issues 3–4, (2009).

[3] Involved were: The Earth Observation and Remote Sensing Group at the Institute for Environmental Engineering (IFU) at ETH Zürich; the Laboratory of Hydraulics, Hydrology and Glaciology (VAW) at ETH Zurich; WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF Davos)

[4] Glacier and Permafrost Hazard in Mountains external pageGAPHAZcall_made

[5] Rapid Mass Movements external pageRAMMScall_made

Contact persons:

Dr. Silvan Leinss, , +41 44 633 40 45

Dr. Yves Bühler, , +41 81 417 01 63

Prof. Daniel Farinotti, , +41 44 739 25 04