Failed civilizations, food bubbles and satellites

No matter how sophisticated and innovative, the ultimate success of any society comes down to the ability to feed its people. There is no greater challenge. There is no greater threat.

The ancient Mayas, populating the Yucatan Peninsula of Central America and beyond until the beginning of the 10th century A.D., were arguably one of the most brilliant civilizations. Breathtaking architecture, a remarkable knowledge of astronomy, sophisticated written language and the Mayan calendar are just a few of the things we remember them for. But then — in what felt like an instant — a society of some 15 million people quickly decayed and eventually disappeared. How could this happen?

One of the most credited theories points to climate change. As suggested in a study1 by Gerald Haug and colleagues, a century-scale decline in rainfall put a general strain on resources in the region. Abrupt drought events reduced these resources further. A growing population, environmental degradation from deforestation and intensive agricultural practice as well as failure to adapt paved the way for a dramatic water and food crisis.

Now, it takes very little associative thinking to see disturbing parallels. With the latest UN report forecasting the world's population to reach 8.9 billion people by 2050, climate extremes repeatedly bringing farmers around the world to their knees and food production becoming just another stock market index, one wonders: could it happen again?

Understanding and foretelling

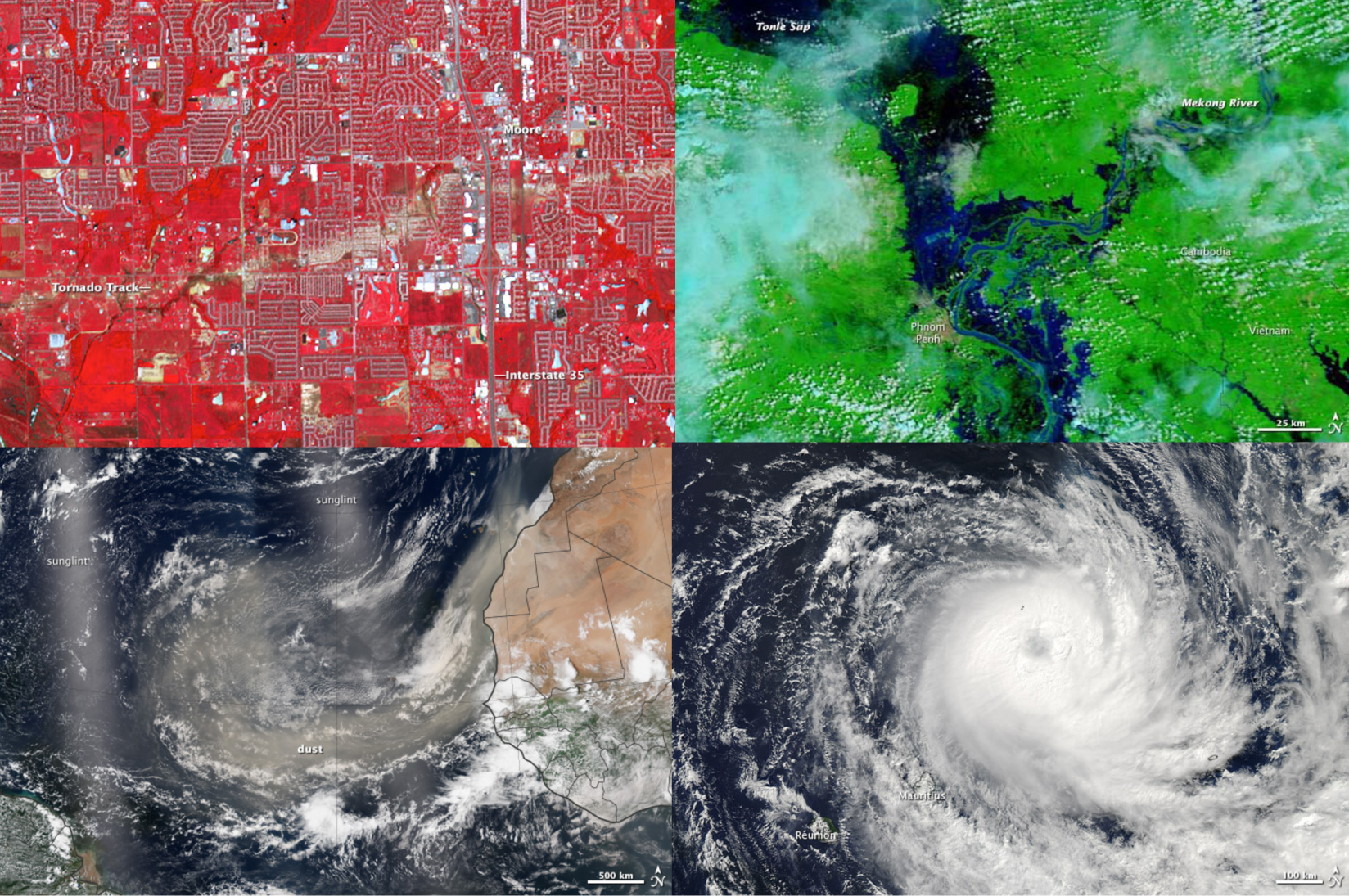

Yet something is fundamentally different. Today, the study of the Earth system by remote sensing satellites helps us understand the signs foretelling a problem and decide whether action is required. In a global context where access rather than availability is the key to determining food security, remote sensing satellites provide reliable monitoring across space and time.

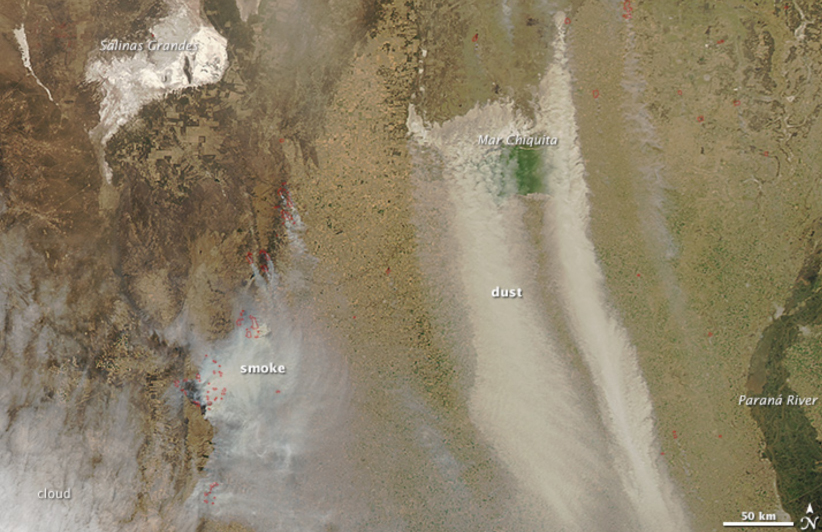

High-resolution satellite image time series spanning over decades document land cover changes such as the dramatic transformation of our fertile land into deserts. Shifting precipitation patterns and warming are causing extended droughts over large parts of currently habitable or arable land. Coupled with aggressive ploughing and land mismanagement, these climatic changes have led to soil erosion threatening the productivity of one-third of the world’s cropland. Dust bowls2 stretching across central Africa and across northern and western China are already visible to the naked eye on satellite images. By mid-century, dust-bowls are predicted3 to appear across some of the most populated areas on Earth — including southern Europe and the US Southwest.

While with one hand we are busy plundering our soils, with the other we are drying out our wells, depleting underground aquifers4 to grow food in places where crops would not be able to grow naturally. Satellites mapping delicate variations in the planet’s gravity, which indicate the presence of large pools of water like aquifers, show falling groundwater tables as irrigation is using up water faster than it can be replenished. In the short run, food production is being artificially inflated by irrigation practices. But in arid regions like Saudi Arabia or in regions being fed with grain produced by overpumping, like China and India5, this has created water-based food bubbles.

Signposts to future food security

Although observing our planet through remote sensing satellites will not help us recover lost resources, it allows us to anticipate trends. Satellite data provides us with information that may help us decide how to go about our next move in an increasingly hungry and thirsty world. We can expect that with a warming climate our major agricultural areas will face losses. However, with climate change influencing agriculture differently at different latitudes, new growing regions are likely to emerge at high latitudes where temperature becomes less of a constraint and the growing season is likely to lengthen as a consequence. The wealth of satellite observation data spanning the last three decades allows us to carefully monitor this trend even at high latitudes, quantifying shifts of vegetation phenological dates6 in relation to regional climate information.

The fight against hunger is recurrent in all great past civilizations. However, the means at our disposal today are unprecedented. The privileged view provided by Earth observation satellites reveals the impact of food systems on the environment and the effects of climate change, which result in threats to the way we grow food today, but it also reveals new possibilities for growing food tomorrow. Ultimately, it is what we as a society make of the information derived from satellite images that will define food security in the near future.

Weiterführende Informationen

1 Haug G et al, Science, 2003: externe SeiteClimate and the Collapse of Maya Civilizationcall_made

2 Romm J, Nature, 2011: Desertification: externe SeiteThe next dust bowlcall_made

3 Dai A, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: externe SeiteClimate Change, 2010: Drought under global warming: a review.call_made

4 Gleeson T et al, Nature, 2012: externe SeiteWater balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint.call_made

5 Rodell M e al, Nature, 2010: externe SeiteSatellite-based estimates of groundwater depletion in Indiacall_made

6 Gonsamo A et al, Journal of Geophysical Research, 2012: externe SeiteLand surface phenology from optical satellite measurement and CO2 eddy covariance technique.call_made