China’s rise as a new AI superpower

China intends to be the world leader in artificial intelligence (AI) by 2030. As part of her doctoral thesis, political scientist Sophie-Charlotte Fischer is analysing the current Chinese upswing in AI.

When Emmanuel Macron announced France’s new national strategy for developing artificial intelligence (AI) on 29 March 2018, it felt like Europe had suddenly woken from a deep sleep. Over the next five years, the French government plans to invest 1.5 billion euros in AI research and related start-ups. “Macron realised he had to do something to stop the continent being left behind in the AI race,” says Sophie-Charlotte Fischer, political scientist and doctoral student at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich.

Breathtaking ambition

One of the reasons for Europe’s newfound interest in AI was the publication of China’s “Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan” (AI Plan) in July 2017. This contains some breathtakingly ambitious goals on the part of the Chinese government, including closing the technological gap with the West in the field of AI by 2020, transforming China’s AI industry into a world leader worth 60 billion dollars by 2025, and achieving global dominance in AI by 2030.

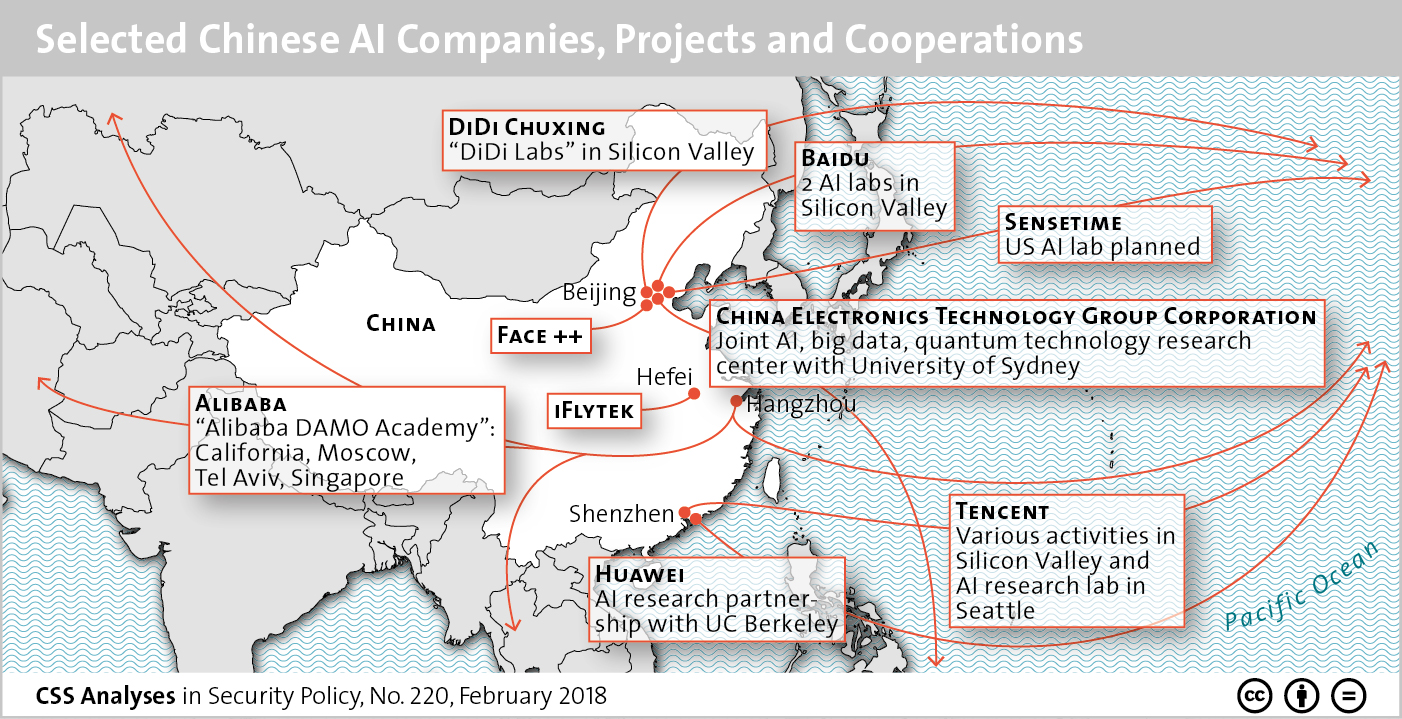

In a recent CSS analysis, Fischer examined China’s rise as an AI superpower. This process is already well underway, with researchers in China publishing more pieces on AI than their counterparts in the US – even though US publications still rank significantly higher in terms of impact. Virtually all the major Chinese tech companies have set up research laboratories in Silicon Valley. These include the tech giants Tencent (messaging), Baidu (search engine) and Alibaba (e-commerce), all of whom are investing heavily in AI.

The Chinese government provides targeted support to help companies establish themselves in Silicon Valley. Between 2014 and 2017, Chinese companies also invested over 13 billion dollars in the ICT industry in the US. Another new development is the increasing tendency for researchers who have studied at American universities or worked in Silicon Valley to head back to Beijing or Shanghai, tempted by lucrative offers from Chinese tech companies and universities.

“For Silicon Valley, it’s time to get paranoid,” warned The Economist in February. Yet Fischer views the announcements coming out of China with a critical eye, despite the country’s rapid progress. “The most powerful microchips for AI applications still come from the US,” she says, noting that the total market volume of Chinese tech companies is only 32 percent of that of American tech companies. She does, however, accept that China may succeed in pushing through its AI standards globally in the medium term, based on its domestic market of 1.5 billion potential users.

AI for weapons and surveillance

China’s ascension as an AI superpower is causing concern, especially in the US. “Artificial intelligence can be used for both civil and military purposes,” says Fischer. Yet, unlike conventional dual-use technologies such as nuclear power, it is hard to control the development and dissemination of AI. Most research publications are published as open source, which means anyone can access them. China has benefited from this situation, as well as from a transfer of knowledge by US-based Chinese researchers. US politicians are increasingly concerned that the purchase of American start-ups by Chinese investors could result in important military technology falling into Chinese hands.

As well as AI’s potential military use, political commentators and human rights activists also highlight a further risk, namely China’s stated strategic goal of using AI to “maintain social stability”. This has set alarm bells ringing against a backdrop of increasing political repression and social control under the current leader Xi Jinping. China’s roll-out of its Social Credit System show how surveillance and AI can go hand in hand: a number of Chinese cities have already introduced systems to continuously evaluate people’s behaviour using video cameras and image data from government databases as well as personal data from the Internet.

Those who demonstrate the kind of behaviour encouraged by the government obtain benefits such as better terms for bank loans and easier access to good schools. In contrast, those who behave suspiciously may find they are no longer able to leave the country. China already has 176 million surveillance cameras and plans to add a further 450 million by 2020. Fischer is one of many experts who believe that the ability to combine this data with advanced AI “has the potential to create an Orwellian model of total surveillance.”

Cooperation and competition

While politicians and civil society have reservations about China’s AI boom, American tech companies are showing a great deal of interest in this new emerging market. Last December, Alphabet (Google) announced its intention to open a new AI research centre in Beijing – even though Google’s search engine and email service are both blocked in China.

Fischer is convinced that the Chinese market is becoming more important for AI companies in the West. “The Chinese have an even greater cultural affinity for new technologies than we do,” she says, based on her experiences during her own trips to China. “Even in rural parts of China, there are lots of places where people pay using their smartphones,” she adds, noting how this enables companies to rapidly test out new developments in real-life applications. With 731 million Internet users – most of whom divulge more data than users in the US – plus lax data protection laws, China offers extremely fertile ground for new developments.

Fischer therefore warns against adopting too much of a one-sided perspective on the intercontinental relationships involved. “Chinese and American companies alike benefit mutually from progress in both countries,” she says. “The evolution of AI is characterised by cooperation as well as competition.”

You can download the CSS analysis “Artificial Intelligence: China’s High-Tech Ambitions” by Sophie-Charlotte Fischer for free here.