Progress and shared prosperity

We should not adapt work to technology but, conversely, find ways in which technology can benefit everyone. Not least for economic reasons, says Gudela Grote.

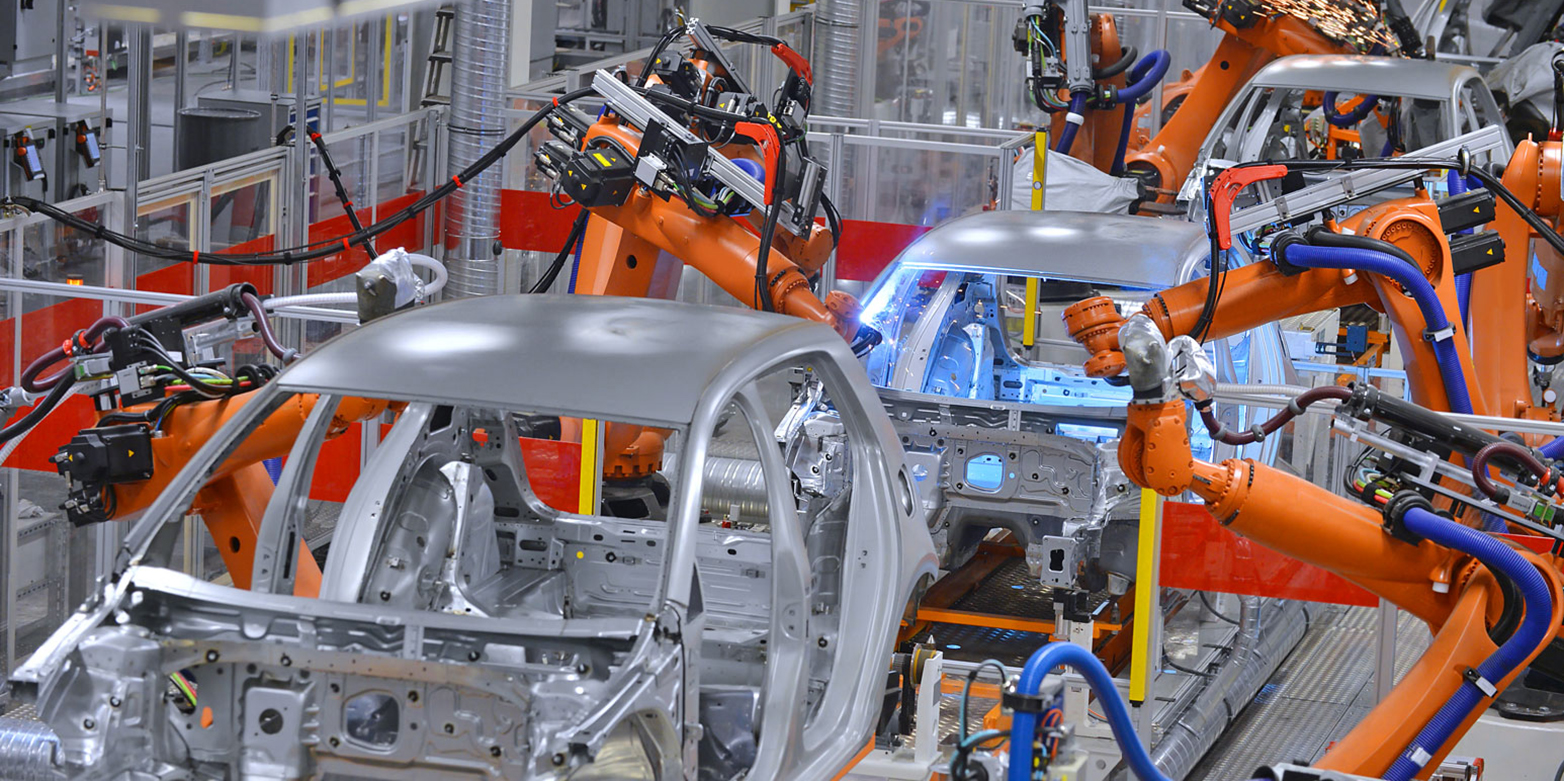

We’re on the brink of several fundamental technological breakthroughs. Autonomous driving, fully automated manufacturing, and home care delivered by robots are no longer the stuff of sci-fi movies. The most striking and controversial innovations concern robotics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning: these areas will require us to interact with technical systems that truly live a life of their own.

Many countries have put digitisation at the top of their agenda for education, employment, and social and economic development. And that’s caused a lot of concern: Will jobs be cut? Might entire occupational categories disappear? What if the requirements for training, qualifications and job profiles completely shift?

Who influences whom?

Too often, it’s assumed that technology will chart its own course, and workers and society will just have to adapt. We take a different view. People design technologies. Societies shape the institutions and policies that influence how technology is used, who benefits, and how those who bear the costs of change can be compensated by those who reap the benefits.

All parties involved in the current debate on the future of production and work should take a step back and question the premise that technology can’t be influenced. We need to ask what motivates technological innovation, and then discuss how to steer it towards creating greater economic prosperity and decent work for all.

«Firms often seek to automate their way out of productivity and labour problems.»Gudela Grote

More direct contact is also called for: engineers and scientists should engage with the users and consumers of their products. This could mean putting workers in touch with design experts to explore ways technology can be used to improve the production process and encourage sustainable growth. There should also be more dialogue within the companies themselves: within the context of social partnership, for instance, employees should be personally involved in important decision-making processes.

What we can learn from the automobile industry…

We believe that, in the past, manufacturing firms have tended to over-invest in automation without paying enough attention to social issues. They’ve often sought to automate their way out of productivity and labour problems.

In the 1980s, for example, General Motors spent over $50 billion on robotics in an effort to catch up with more efficient Japanese producers. Yet it ended the decade as a high-cost producer because it failed to invest in its workforce and change its work practices in ways that made the new technologies pay off. Meanwhile, Toyota achieved world-class levels of productivity by introducing new technologies gradually, while simultaneously investing in team-based work systems and high levels of workforce training.

…but unfortunately not everyone does

While we might assume that top executives have learned this lesson, apparently Elon Musk at Tesla has not. Ironically, in the same plant in Fremont, California where Toyota achieved high levels of productivity by gradually introducing technology and working with workers and their union, Tesla is failing to meet its production goals. Just why is Tesla falling behind? Because the company is pursuing a total automation strategy. And, not surprisingly, workers at its factory are trying to organize a union in protest of what they see as persistent safety problems, overwork, and low wages. At the same time, investors are worried that the company’s cash reserves are running low. And this, as we know, has led to Elon Musk’s announcement that he will cut some 3,500 jobs.

Similarly, criticism has been levelled at the 15 manufacturing technology centres the US government is putting in place along the lines of the German Fraunhofer Society. Despite the promise that the state programmes would also promote vocational education and training, initial evaluations show that investments were made primarily in technology development, with training taking a back seat. The one exception is the programme on lightweight construction: here companies and vocational schools are together tackling technology development and training, and combining both.

Researchers and manufacturers all over the world are beginning to adopt this more inclusive approach to technology. Major research institutions such as MIT and ETH Zürich are setting up task forces to tackle the issue. But many tough questions lie ahead. If we can launch a dialogue across all social groups and institutions on which technologies should be used and how to create benefit for all, we will have taken a crucial first step.

This is a slightly adapted version of a text that first appeared on the external pageWorld Economic Forum websitecall_made. It was written by Gudela Grote together with Thomas Kochan, Professor of Employment Research at the MIT Sloan School of Management.