Tapping into underground urban heat islands

Cities are heat islands – not only above ground but below ground too, and therein lies the enormous potential to better harness this energy through geothermal heat exchangers. A group of researchers demonstrated this in a case study conducted in the city of Zurich.

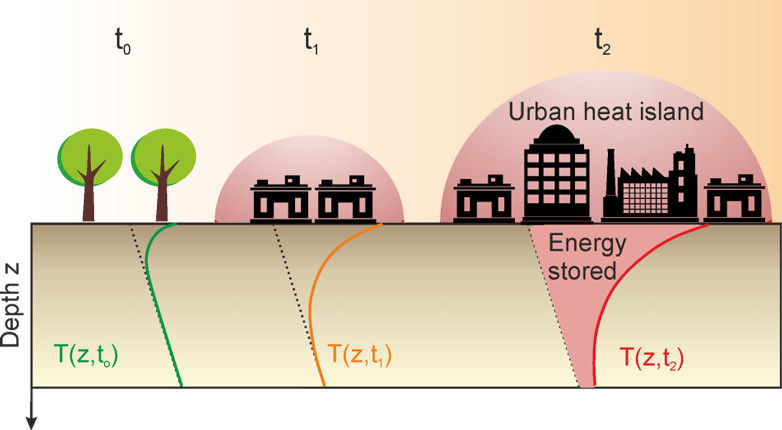

Cities and densely built-up areas are warmer than their environs. This is particularly noticeable on hot summer days, when the heat builds up between the buildings and streets radiate sweltering heat. The air outside the city is often noticeably cooler.

But cities are not just heat islands on the surface; the ground below built-up areas is too. The heat dissipates into the ground through the streets, cellars, underground garages and sewers. This heat input can be considerable; for example, in the city of Zurich, 20 metres underground, it is several degrees warmer than at the same depth outside the city.

Heat input regenerates the natural reservoir

In an article published in the journal Renewable Energy, a group of researchers, including ETH earth scientist Jaime Rivera, demonstrated that these subterranean heat islands harbour an as yet untapped potential source of energy production. This potential could be tapped with systems already used for the collection of geothermal heat.

Thus, Rivera and his colleagues used a model to calculate that the potential for the use of geothermal heat in urban areas is much greater than in rural areas due to the island effect – up to 40 percent higher.

The extra heat stored in the ground also regenerates the natural heat reservoir in the soil, which can be tapped using geothermal heat exchangers. By exploiting only the underground thermal energy surplus, geothermal systems in urban areas can be used for longer periods and more intensively than if only natural heat is used. “If the use of surplus geothermal heat is moderately intensive, the waste heat from urban structures is sufficient even to regenerate the natural heat reservoir,” says Rivera, lead author of the study.

More energy, shallower drilling

Thanks to the surplus heat input, more thermal energy could be collected from the ground and the length of the drill holes shortened. “Each additional degree Celsius at the urban ground surface means the borehole required to collect the same amount of energy can be four metres shorter,” explains the earth scientist.

In order to test their model, developed to calculate the heat usage potential, the researchers used an example from the Zurich metropolitan area. In addition to the increased heat flux from the island effect, they also included atmospheric warming due to climate change.

“Our findings will be helpful in the planning of geothermal energy systems in areas with elevated soil temperatures,” says Peter Bayer, who is leading the study. Cities also have other heat sources that contribute to soil warming, such as tunnels, sewers and district heating systems. “But since all these heat sources are artificial, strictly speaking we’re not exploiting a naturally renewable energy source,” emphasises Bayer.

Geothermal heat

Geothermal heat pump systems are the most common type of geothermal technology in Switzerland, normally with boreholes of about 150 metres – even deeper in cities. A heat exchanger – usually two U-shaped pipes through which a fluid circulates – is installed in the borehole. This fluid absorbs heat from the ground and then transports it to the surface. An (electric) heat pump uses the thermal energy in a building to heat rooms and process water.

Reference

Rivera JA, Blum P, Bayer P. Increased ground temperatures in urban areas: Estimation of the technical geothermal potential. Renewable Energy 103 (2017) 388-400, doi: external page10.1016/j.renene.2016.11.005call_made