An ordinary day on an extraordinary expedition

Good weather and lack of pack ice allow Akademik Treshnikov to travel to Mount Siple on the Ross Sea Coast before completing the second stage of the expedition. Iris Thurnherr reports on daily routines and exceptional situations during her fourteen-week stay on the research vessel.

You might think that after three months on Akademik Treshnikov, our expedition around the cold continent would now be as dull as the vast expanse of ice and the rough sea surrounding us. And yes, much has become routine: every day I check the equipment for measurements, every morning I call up the latest weather report from colleagues at ETH, every afternoon we work out on the helicopter deck, at regular intervals we launch weather balloons, and every evening I check that all is well secured in the lab.

But daily life on the research expedition is far from boring; the voyage presents us with a stream of sensations and experiences that punctuate the routine. On the second leg of our journey, our surroundings gradually change from the dark-blue ocean to light-blue ice, and from rain to snow. There are icebergs of changing blues and weird shapes, amazingly long sunsets which bathe the icy landscape in a mystic light, chattering penguins and lethargic sea lions on drifting ice floes. It all never ceases to fascinate.

Chasing snowflakes on a windy deck

And of course there’s our research into the water cycle in the Southern Ocean (see ETH News and blog). Together with two colleagues from Aveiro University in Portugal und Brown University USA who are studying the influence of rainfall on the salt content of the ocean, I’m now collecting snowflakes. Later, in the lab, we’ll measure the behaviour of water isotopes in the samples.

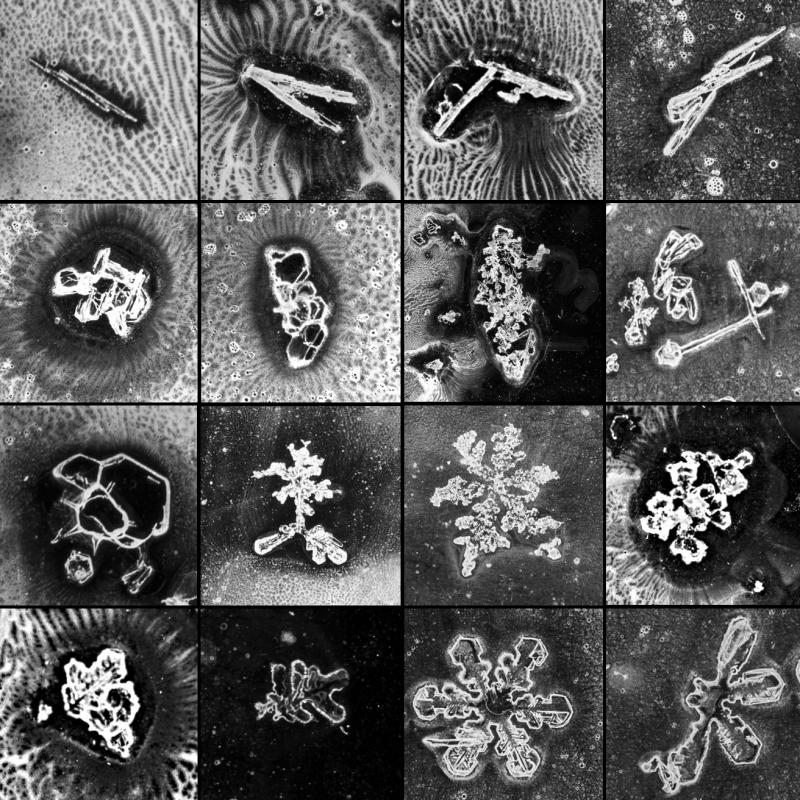

Easier said than done! Catching snowflakes in sufficient quantity is rather more difficult than collecting raindrops. The wind and the motion of the ship keep whipping up the airy flakes – instead of gently falling onto the deck, they fly off sideways and drift up along the ship’s side. Nevertheless, we attempt to catch individual flakes in the air, for a successful catch reveals the multi-faceted forms of these delicate crystals – they change shape from one time to the next, and have very varied patterns even within a snowfall. Observations such as these help lighten the long stints spent collecting.

Valuable information in the snow

The snowfall is as fickle as the snowflakes are fluttery; it’s much more difficult to predict than rainfall. I pore over the weather forecast for hours, trying to work out when snow will fall next, only to be surprised again in the middle of the night. Thank goodness for my two colleagues, who help me keep an eye on the weather, striving not to miss a single incident.

A while later, feeling over-tired and exasperated, I mull over the weather forecast again. This time I’m trying to work out when the snow will stop – it’s been falling for 36 hours and my strength is waning! At moments like these, a glance at the line-up of bottles with melted snow samples, and the thought of that valuable insight into the water cycle of the Southern Ocean raise my spirits – I keep watch for the onset (or finish) of snowfall with renewed motivation.

Fair weather is fascinating too

It’s true, I’m happy for the sunny, calm weather over the last couple of days – it has given me a chance to recover from the snow-collecting marathon! And from a meteorological point of view, this period is interesting too: dry air from the Antarctic flowing over the Southern Ocean causes water to evaporate, and we can measure this evaporation based on isotopes. Seeing the process in my mind’s eye, I scour the wide sea for fresh evaporate in the atmosphere; but it cannot be seen. Only once the water molecules condense into tiny droplets and form cumulus clouds the water becomes visible again.

Stop-off at Mount Siple

Thanks to the good weather, we can make an unscheduled stop at the Siple Coast, the middle portion of the Antarctic coastline before the Ross Sea. Towering over the landscape here is Mount Siple, a scarcely explored volcano that rises to over 3,000 metres. The coast is usually blocked by pack ice, but right now it is accessible, and all 22 project teams can take their samples. Everything is worth collecting – from ice cores and snow, to moss and insects. And while some researchers count penguins, others examine the creatures living on the ocean floor.

On our last evening at the Siple Coast, the full moon rises behind Mount Siple, bathing the ice in a pink glow, and casting a warm light on this beautiful yet barren part of the world.

A wistful look back

Three months on board ship is a long time! I’m impressed by those colleagues who are travelling on from Punta Arenas to tackle the third and last leg of the expedition. My days on board Akademik Treshnikov are now numbered, and I feel rather sad that this exciting journey will soon be over. Seldom have I observed the weather so intently, experienced each snow and rain shower so closely, and been so delighted (or infuriated) with measuring devices. Never before in such a short time have I met so many inspiring people or felt my limits so acutely!

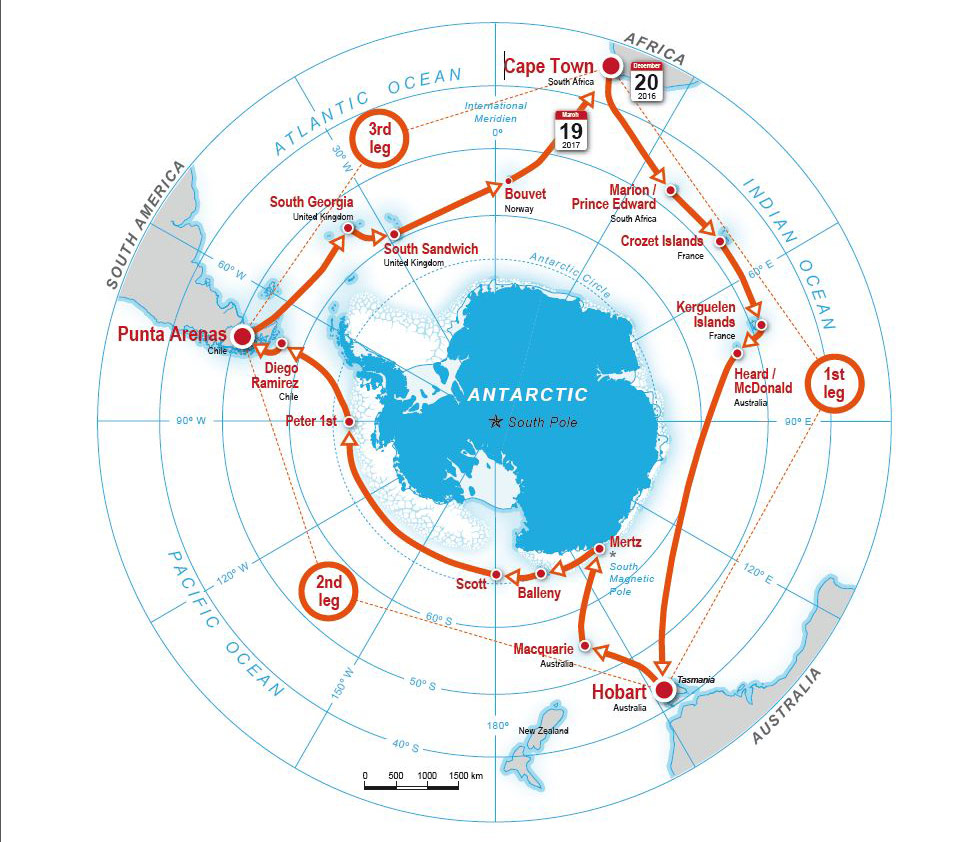

A series on the Antarctic expedition

The researchers from the Swiss Polar Institute’s Antarctic Circumnavigation Expedition (ACE) arrived in Punta Arenas, Chile, where the second leg of their journey ends. Now the Russian icebreaker Akademik Treshnikov is about to enter the third and last leg, sailing from Chile to Cape Town. ETH researchers on board are recording their experiences in the Zukunftsblog.

Further information: external pageSwiss Polar Institutecall_made, external pageACE Facebookcall_made , external pageACE Twittercall_made, external pageSchiff-Trackercall_made.