Memorable field trips

To some people, a field trip may sound an outdated concept, but at ETH Zurich this teaching method is used on many courses. Students and lecturers both agree that content learnt on field trips sticks in the mind particularly well.

In mid-July, Davos is wet, cold and uncomfortable. At 2,000 metres above sea level, there’s nothing but snow. But that doesn’t stop a dozen students, assistants and three professors from the Department of Environmental Systems Science (D-USYS) from embarking on a field trip. ‘Soils and Vegetation of the Alps’ is the subject – but the weather forces them to change the programme. Instead of plants beyond the treeline, the students will study the soil profiles and vegetation below it: a spruce forest on acidic, nutrient-poor ‘podzol’ and a pine forest on serpentinite rock.

While the group listens to Matthias Baltisberger, professor of geobotany at ETH, many students have an eureka experience: the many seedlings of a mountain pine, which protrude from the serpentinite rubble alongside the mother tree; the debris that was carried into the valley by a mudslide a few years ago and now gives way beneath each step; the continuous rainfall, which can trigger such mudslides – the various impressions condense and become etched in the memory.

Learning with all five senses

This is one of the reasons why field trips are so important in many departments at ETH Zurich. Whether they’re studying agricultural, food or earth sciences, architecture, mechanical and civil engineering, study field trips are as popular as ever among students. They range from tours of the Gontenbad mineral water plant in Appenzell to week-long seminars at the Singapore-ETH Centre in Singapore. For participants, field trips are the highlights of the course.

‘Going on a field trip’ may sound like an old-fashioned or antiquated concept, but for botanist Baltisberger, they are simply the best method of teaching students about plants and their ecology. “There is no other teaching format that enables students to absorb so much material so easily. Study field trips are – quite literally – an impressive teaching method.” Baltisberger sees field trips as “our most valuable lesson time”. They allow the theoretical content taught in lectures to be demonstrated and applied in a hands-on environment. No other teaching method allows the course material to be experienced with all five senses: “Plants can be seen in their natural environments. The students can smell, touch, chew or even eat them. And some species even have acoustic properties.”

This opinion is shared by another member of the Davos field trip group, Ruben Kretzschmar, professor of soil chemistry at D-USYS: “Seeing pictures of soil profiles in lectures is simply not the same as studying them in the field, where the information is remembered more easily.” A field trip brings the abstract material from a lecture to life.

Break from the normal study routine

Students also appreciate the value of study field trips. Environmental engineering student Matthias Gmür is taking ‘Flora, Vegetation and Soil of the Alps’ as an optional module on his Master’s course. He has already been on several field trips on different topics, “from visiting a construction site to this one about Alpine flora”. He sees field trips as a good opportunity to take a break from the normal study routine and learn things in a different, more memorable manner.

“I can consolidate and apply the theoretical knowledge learned in lectures,” adds Martin Kistler, a student of environmental sciences. Kistler believes field trips are important for environmental scientists in particular, as they give students the chance to see for themselves the facts they hear about in lectures. It makes students realise that transitions are smoother in nature, not quite as schematic as shown in textbooks. In his opinion, this is an important experience.

Good and bad field trips

Kistler’s course offers a good range of field trips and generally a wide choice is offered in the area of environmental sciences, he says: “It’s great that there are so many field trips.” And his own experiences have all been good so far.

But what makes the difference between a good field trip and a bad one? In Kistler’s opinion, “a field trip is bad if it has been poorly organised”. Gmür adds: “Or when the expert who has been brought in especially for the field trip knows less than the students.” The quality of a field trip depends on the people, professors and assistants taking part. They must be able to explain things well and they must be committed. “If they are passionate about their subject, the learning will take care of itself on a field trip.”

Time and personnel-intensive

Last but not least, a field trip is also about students getting to know each other better and making new contacts. “Students meet people in the same semester, with whom they can study for future exams,” says Constanze Conradin, who used to go on botany field trips as a biology student some years ago but now looks after students as an assistant. Gmür adds: “The distance between students and teachers becomes narrower. On a field trip, a professor who we only know from the lecture theatre is now walking alongside us.”

The teaching staff also appreciate this closeness: “Because the groups are small, the students receive more intensive, individual support,” says Baltisberger. He believes that social learning and experiences are part of any study field trip, but this has a drawback: field trips are time and personnel-intensive. Nevertheless, the professor, who is retiring in 2016, wants to see this teaching method continue or, better still, used even more in the future. “No computer tool in the world, no matter how well it has been set up for learning, can take the place of experiencing the material at first-hand outdoors.”

Memorable field trips

-

Assistant Simon Crameri explains the characteristics of the bladder campion (Silene vulgaris) to his students: field trips depend on the commitment of the teaching staff. -

ETH professor Ruben Kretzschmar uses a profile to show the characteristics of soil above acidic rock in a damp climate. -

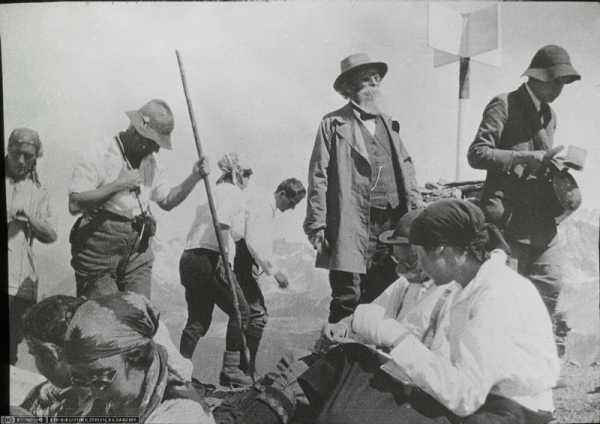

Field trips have a long tradition at ETH Zurich: here, the legendary Alpine botanist Carl Schröter is with his students in Zermatt in 1922. (Image: e-pics / ETH Library) -

Differences between the Common Bilberry (left) and the the Northern Bilberry (right) are subtle but noticeable.